How the Detroit Zoo's first day was almost its last

By Kay Houston

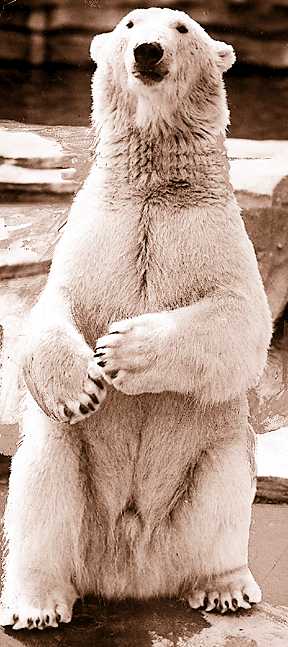

The Detroit Zoo has become the most popular place in the metro area for parents to spend a day with their children. But its opening day in 1928 could well have been its last if zoo attendants had not prevented a surprised polar bear from eating the acting mayor of Detroit.

Acting Mayor John C. Nagel was to be the main speaker at the zoo's official opening Aug. 1, 1928. He arrived late, parking in back of the bear dens. As he came rushing around the front, Morris, a polar bear, leaped the moat to reach some bread left there by a keeper and came face to face with Nagel.

Nagel, not familiar with the ferocity of polar bears, stuck out his hand and walked toward the polar bear joking, "He's the reception committee."

Fortunately for Nagel, the keepers rushed the bear, forcing him back. The book "The First Fifty Years" by William A. Austin, commented on the near tragedy: "It is mind-boggling to conjecture the future of the Zoo if it had marked its opening day with the consumption of the City's executive officer by one of its stellar exhibits, in full view of a grandstand packed with spectators".

The forerunner of the Detroit Zoo had an even more ignominious beginning. It was established near the current site of Tiger Stadium in 1883 with a collection of animals that had been abandoned by a bankrupt traveling circus. This incarnation of the Zoo was forced to close the following year because of financial problems and because the animals kept disappearing. It seems that Detroiters were stealing them.

It took another 28 years before a second attempt to establish a permanent zoo was made. In 1911, a collection of Detroiters whose names read like a street map of Detroit -- Larned, Hurlbut, Ford, Bagley, Joy, Chalmers, Denby, Rackham, Ledyard, Briggs, Follett, Burroughs, Scripps, Alger...and more -- formed the Detroit Zoological Society to plan a first class zoo.

The Society first bought land in 1914 in Dearborn and Ecorse, but it turned out to be land that Henry Ford coveted. He offered the society a good price, so they sold it to him and used the profits to buy land north of Six Mile. This land was also resold at a profit and in 1916 the society purchased the Hendrie farm between 10 and 11 Mile roads west of Woodward -- the current site of the zoo. The Detroit Zoological Park Commission was established in 1924 and construction began.

The society was an early proponent of recycling. The central area of the zoo, the Mall, was filled in with thousands of yards of sand from excavation for the Royal Oak Washington Square Building; building materials elsewhere in the park were taken from the dismantling of the Pier Ballroom at Belle Isle.

Much credit for the design of the zoo goes to Heinrich Hagenbeck of the Hagenbeck Zoo in Hamburg, Germany, who was brought here as an advisor. The exhibit areas followed a moat-like design, placing the animals in what looked like their natural habitat. It was this concept that gave the park a unique place among zoos in the United States.

Zoo Director John Millen announced at the end of 1927 that the zoo would open in the summer of 1928. The pace of building was stepped up, but as more and more animals arrived, workers were told that if they didn't finish the dens they would have to house the animals in their homes. Fortunately the Bird House, Lion Dens, Raccoon and Wolverine Exhibits, Bear Dens and African Veldt were completed before the deadline, so the workers did not have to open their homes up to unwelcome guests.

Paulina, the elephant, arrived in June of 1928. In time she would become a star attraction at the zoo, but at the moment she provided much needed help with the construction projects.

The new zoo delighted the crowds. On the first Sunday, August 5, 1928, almost 1,000 entered during the first 15 minutes. More than 120,000 people came through the turnstiles until they were ordered taken out to speed up the flow. Visitors broke through the fence along 10 Mile Road in two places and streamed through. The 150,000 estimated attendance may have been exaggerated but no one denied that opening day was a huge success. The following Sunday's attendance was even higher and 2,734 people took rides on Paulina the elephant.

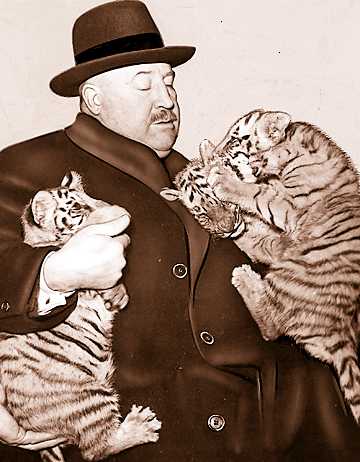

The most popular exhibit were a set of 21-day-old lion cubs. By the end of the year, the zoo was an accomplished fact and definitely part of the Detroit scene.

When the Depression hit in the fall of 1929, it also hit the Zoo. That winter the snow was so heavy, a horse was used to pull a sled with food to the animals. More than 70 tons of ice was stored to be used in refreshment stands in the summer. With funds scarce, employees went to nearby farmland to harvest timothy hay to feed the animals. The frugal zoo operators got materials wherever they could, including 100,000 feet of lumber from the Detroit House of Corrections that was being torn down, and whatever they could glean from condemned buildings.

In 1931 a miniature railway system was donated to the zoo by The Detroit News. William Scripps, president of The Detroit News, made the presentation on opening day and took the first ride. The fare was a nickel, with any profits to be used to maintain the system. As popular as it was, problems also rode the rails: the train often ran off the tracks. When it did, passengers got their nickels back. Nearby residents complained of the noise and at one point the train ran on rubber wheels.

Despite its popularity, the zoo was a frequent target during the depths of the Great Depression. Activists complained that while Detroit starved, idle animals lived in luxury. Some threatened that the people of Detroit might be eating the swans and monkeys before 1931 ended.

Another group wanted the zoo turned over to them so they could charge admission and make a profit. Commissioner James Holden refused to charge admission. He said it was one of the few places people could go to escape the gloom and doom of the times.

But in 1932-33, the zoo's one-mill tax was temporarily suspended and the zoo was forced to start charging for services, such as 25 cents to park and a nickel to ride Paulina. Other money saving measures included the exchange of surplus animals with other zoos and animal dealers, and the cultivation of a large truck farm at the zoo that grew animal feed.

The zoo started charging rent for housing animals from dealers and circuses temporarily. Several government agencies gave funds to the zoo to hire jobless workers to build new exhibits.

Despite many financial ups and downs, by the end of 1938, the zoo boasted a collection of 481 major mammals of 61 species, 176 minor mammals; 800 waterfowl and 500 birds. The reptile collection numbered 30 alligators, 24 turtles and 218 snakes.

The first lion cubs born at the zoo in 1928 were named after Walter O. Briggs, to commemorate his gift to the zoo. The male cub was called Walter and the females, named after his daughters, were Jane and Susan. Lions were never an endangered species at the zoo as they multiplied rapidly. A September 1930 News article told how director Millen was tearing his hair out over the latest births, "trying to figure out how he was going to buy 27 dead horses to feed the lions when the city only allowed him enough to buy 18 carcasses."

In August,1929, two giraffes arrived from Africa, named Neck and Neck. They had to be transported from New Hampshire to Detroit in specially constructed giraffe railroad cars. According to a News article of July 1929, the floors of two flat cars were lowered 2-1/2 feet and a small deck house was mounted on each car to afford a neck rest.

"While the train track is clear,", the story said, "the giraffes will be permitted to stretch their necks at will and look over the scenery. As they approach a low bridge or tunnel, the (keeper) will reel in the giraffe's neck and attach it to the padded rest until the passage has been made safely. When they get to Detroit, they will have two taxis awaiting them which are actually underslung trailers ordinarily used to transport steam shovels."

Queenie, the handsome big Siberian tiger, gave birth to two beautiful cubs in May of 1935 but they died shortly after from too much love. She fondled them and licked them constantly, depriving them of sufficient opportunity to get regular meals. One died and by the time the keeper got the other one away from her, it was too late.

Queenie met a tragic end a few months later. She and another Siberian tiger, Nellie, were about to lounge in their pool when Nellie sank her teeth into Queenie's shoulder, killing her.

A year later Nellie grabbed a male tiger by the throat, killing him. From then on she was kept in solitary confinement.

A December 1935 Detroit News article talks about the difficulty of raising polar bears in captivity.

"The recently born cub is one month old. The keepers don't dare approach too closely or the mother will kill the cub; another danger is that the mother often accidentally sits on the babies, killing them." Until that time, only the Milwaukee Zoo had been able to raise a polar bear through its first season. In March of 1936, "Little Joe", as he had been named, made his debut at the Detroit Zoo, peeking from behind his mother's legs, becoming only the second bear in the U.S. to be born and raised in captivity.

Some zoo milestones:

* Sammy, an Indian elephant given to the zoo by Ringling Brothers, had become quite mean and had to be destroyed in 1937.

* Thousands of children rode the large Aldabra tortoises that arrived in 1938.

* That same year the media reported on director Millen's remedy for the chimps' many winter colds -- "carefully measured doses of 20 year old cognac."

* The zoo sold a wolverine to one of the auto companies in 1939 which then gave it to the University of Michigan to use as a mascot for their football team.

* That same year, the Rackham Memorial Fountain was dedicated. It became one of the most famous "meeting places" in the zoo. The fountain was named after Horace Rackham, the first president of the Zoological Commission.

* At the beginning of World War II, there was concern about what would happen if the zoo were bombed and animals were loose. An air raid warden was assigned to work with nearby residents who had firearms in their home. Should an air raid occur, they were to help destroy any animals who escaped.

* The News reported in 1954 that Blackie, a mynah bird stolen from the zoo, was recovered in 1954 after acquiring a few exotic expressions that made him unfit company for children. He was put in solitary confinement and re-educated until his language was acceptable in polite company.

* In 1957, the zoo acquired G. I. Joe, a homing pigeon who had carried a message from an isolated outpost at Colvi Vecchia during World War II and saved more than a thousand British soldiers.

* A headline in the Detroit News in 1957 read, "A Seal with Zeal in a Deal for a Meal. " The story announced the arrival of Roland, the elephant seal who weighed 900 pounds. He had to be bribed with large morsels of fish to pose for photos.

Two of the most famous residents of these early days bear looking at in more detail: Jo Mendi, the chimp and Paulina the elephant.

Jo Mendi was four years old when he came to the Detroit Zoo in 1932 during the Great Depression. Director Millen purchased him with his own funds when the society didn't feel it could spend the money with so many Detroiters in dire straits.

Jo Mendi was a veteran of Broadway and the movies, and he brought his act to the zoo. The Detroit News reported in June 1932 that "Jo enjoys every minute of the act...He counts his fingers, dresses, laces his shoes, straps up his overalls; pours tea and drinks it; eats with a spoon, dances and waves farewell to his admirers."

The admission charge to Jo Mendi's show was 10 cents and brought the zoo a daily profit of $l2 to $20. Jo added to his repertoire while at the Zoo, with such acts as roller skating, bicycle riding, tight rope walking, etc.

Jo became ill in the fall of 1932, causing alarm among zoo workers and visitors and worried surgeons from Grace and Keifer Hospitals came to check him out. It turned out he had swallowed a penny tossed at him during his act. During his recovery, hundreds of visitors brought him everything from toys to peanuts. He received more than $500 worth of flowers and several thousands cards and letters.

Proving that fame is fleeting, the zoo started training four new chimps in December of 1933 to eventually take Jo's place. The keepers explained that as a chimp gets older, his disposition may become rebellious, making him difficult to work with.

Jo continued to bring joy to the crowds until the fall of 1934 when he died after contracting hoof and mouth disease. A headline in The Detroit News of Sept. 8, 1934, read, "Jo Mendi is dead--Jo, the 'greatest dog-gone monkey who ever lived.'" Jo reportedly died clasping the hand of the man who loved him, John Millen, who had sat at his bedside night after night.

Paulina was an Indian elephant who had performed in circuses prior to coming to the Detroit Zoo in semi-retirement. She weighed six tons and her baby daughter, who came with her, weighed a half ton. Too tall for a railroad boxcar, she arrived in a low-set open gondola car.

Shortly after arrival, she was put to work moving heavy construction materials in preparation for the zoo's opening later that year. Workers estimated her hauling capacity was equal to 12 teams of draft horses. Every day she ate 50 pounds of corn and oats and 140 pounds of hay.

In her years at the zoo, she gave rides to half a million people, mostly children.

As the elephant Queen, she supervised new arrivals. When Safari, a young African elephant arrived, he refused to move past the zoo gates. He was shackled to Paulina who pulled him to the elephant house.

Paulina died in 1950 at the age of 69. The Detroit News quoted a zoo worker: "She was so gentle to the end. We all stood about for a few minutes unable to talk...It was a bad time for all of us. Everyone of us felt we had lost a close friend."

In a way, it was the end of an era. She was the last of the original animals.

Alex McDonald contributed to this story.