How Detroit police reinvented the wheel

By Kenneth S. Dobson

Throughout its long history, the Detroit Police Department has been a leader in adopting new technologies in the war against crime. It was among the first departments to put officers on bicycles, it had one of the earliest motorized forces using motorcyles, but perhaps most important of all, it pioneered the use of the automobile and the mobile radio as crime fighting tools.

Detroit's first non-militia peace officers were appointed in 1801 and a night watch patrol was established in 1804. However, it was not until 1863, in the midst of a crime wave, that the State Legislature passed a law establishing a Police Commission for the City of Detroit. In February of 1865, the Metropolitan Police Department of Detroit was established with 40 officers, growing to 51 officers by the end of 1866. In its first full year of operation, the force arrested 3,056 persons.

In the beginning the police were watchmen, patrolling neighborhoods and business districts on foot. The closeness of the cop on the beat to the community created a strong bond between the police and the public they served. But foot patrol had severe limitations. For one, it was difficult to supervise. Beat officers were prone to spending much of their tours sitting inside warm stores chatting with friendly merchants, who were pleased with the security they provided.

As the patrol area increased in size, even a motivated beat officer was unable to cover it in a single tour of duty. Plus, there were critical time lapses between an incident and arrival of the beat officer.

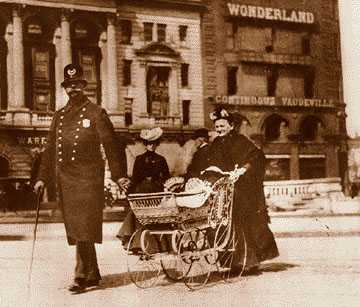

According to 1810 census figures, there were 750 residents in the city of Detroit, which covered a little more than three square miles in area. By 1870, the population of Detroit had increased to 79,577 while the city itself had expanded to more than 12 square miles. As the population increased, and business and residential districts began to sprawl, the Metropolitan Detroit Police Department used open farm wagons to disperse its patrol officers at the beginning of a shift. At the end of the duty-day, the wagon was used to collect the officers and return them to police headquarters.

Prisoners were transported in horse-drawn covered wagons known as "Paddy Wagons." Contrary to popular opinion, the name was not a slur on immigrant Irish but referred to padding on the walls and floor of the wagons to prevent the prisoners from injuring themselves.

In 1897, Detroit police began to use another form of transportation, the bicycle. The first bicycle patrol officers were known as "scorchers." The scorchers were expert bicyclists employed for the express purpose of apprehending other speeding bicyclists.

As the city grew, so did the need for additional police services. The Forty-third Annual Report of the Metropolitan Police Commission published in 1910 indicates that from July 1907 through June 1908 the city's 636 police officers made 788,599 reports, answered 28,245 phone calls and made 11,291 arrests. The following year, the commision's report said the force made 11,676 arrests. The human resources of the department were being strained. Clearly, something needed to be done to improve police response time. The department's solution was motorization.

On Aug. 9, 1908, the Motorcycle Squad was created and was "ready day and night to make a fast response to any call by telephone from any part of the city for a police officer," according to the police commission's 45th Report.

During this same period the automobile was becoming a force in American life. It was viewed by many as a solution to the problems of pollution and congestion caused by the horse.

"In the early twentieth century, the replacement of the horse by the automobile was widely applauded, for it promised a far cleaner urban environment," wrote Rudi Volti in his book Society and Technological Change. "In those days horses in New York City deposited 2.5 million tons of manure annually."

Accidents were common. Adults and children alike were regularly hit or trampled by horses or run over by wagon wheels. Although the automobile was seen as a solution for some of these problems, it soon became clear that it was creating pollution of its own and was adding to the congestion of already overcrowded streets.

But of more concern to police, it was creating new crimes -- stolen automobiles, speeding, vehicular homicides, and a faster means of escape for criminals.

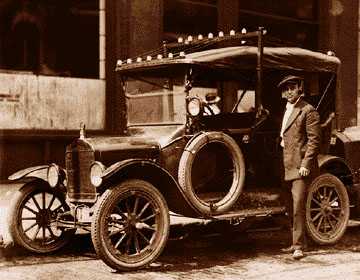

In 1909, Detroit Police Commissioner Frank Croul began testing the automobile to determine the "fitness of such a vehicle for police work." He was so convinced of the need for such a technological tool that he purchased the department's first patrol car, a Packard, with his own money. The use of an automobile for policing was such a radical idea that he was unable to obtain approval for the expenditure of city funds. The Packard cost Croul $350 .

From Dec. 1, 1909 through June 30, 1910, Croul's police vehicle responded to 2,235 police calls.

Croul's tests swayed Common Council and the Board of Estimates and in July of 1910 they approved the purchase of seven patrol cars, a seven-passenger automobile and a truck for the police department. On Jan. 8, 1910, according to an article in The Detroit News, "Henry Calhoun, a plain drunk, was the first passenger carried in the Department's first auto patrol."

Detroit's police force was a pioneer in adoption of the motorcar but its use as a law enforcement tool generally failed to keep pace with the startling proliferation of automobiles among the general public. Early cars were expensive and often experienced mechanical difficulties which made them unreliable.

But with the Roaring 20s came a crime wave that put law enforcement agencies across the country on wheels. Prohibition provided gangsters with a lucrative business -- quenching the thirsts of citizens willing to thumb their noses at the law -- that allowed them to afford high-powered cars.

Outlaws could strike at two or more locations and speed away before foot or bicycle patrols could respond Even if the police were able to arrive in time, the crooks were easily able to outrun the technologically challenged officers. The nature and means of committing crime had changed. Foot patrols and bicycles were no match for automobiles that could race from one crime to another and then speed away.

The Prohibition Era provided the urgency for putting police on wheels across the country, marking the beginning of a dramatic change in the way law enforcement operated. Police were now able to cover larger areas of the city in less time, to vary their patrol routes so that criminals could not easily detect patterns, and to give the impression that they were "omnipresent." They were able to respond to a greater number of calls in less time and with the same number of officers.

But there were still problems in dispatching the cars. From 1910 until 1916, motorized police units were stationed at police headquarters. When a call arrived at the police station, the officers were literally sent out the front door to respond. When they completed their call, they returned to the station to await another call. The cars did not patrol the city's streets because there was no means of communicating with them

In 1917, the Detroit Police Department began deploying motorized patrol units across the city using a "booth car" system. The booth was a small building equipped with a pot-belly stove, a coal bin and a telephone. Two officers were assigned to a car and were stationed at a booth. One officer remained at the booth with the car while the other patrolled the beat by foot .

A dispatcher at police headquarters would contact the booth via telephone lines, often waiting until there were five or six assignments, and dispatch the officers to where they were needed. This procedure often caused the officers, and the car, to be out of contact with the police department for three or four hours at a time.

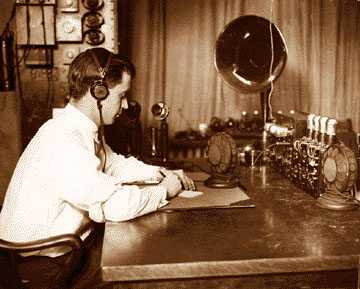

In 1921, Detroit Police Commissioner William P. Rutledge began experimenting with patrol vehicles equipped with radios. Rutledge was "convinced that the automobile had given the criminal an advantage in speed that could not be overcome by police cars controlled by telephone. Gangsters could make their getaway while the booth patrol was still awaiting a telephone call.

Rutledge had a radio transmitter installed at police headquarters and in 1922 the Federal Radio Commission, the forerunner of the Federal Communications Commission, issued Detroit the first provisional commercial radio license, KOP.

But there were obstacles to be overcome before the radios could be made mobile. The vacuum tubes, which comprised the internal workings of the radio receiver, were fragile and required extensive cushioning. The electrical systems of the automobiles were not powerful enough to operate the radios, so six-volt batteries had to be mounted on the running boards. The battery was only good for four hours before it had to be replaced.

Other obstacles were less technical but just as formidable. Several times the Federal Radio Commission refused to renew the department's radio license because it failed to live up to requirements. One of these insisted that KOP broadcast "entertainment during regular hours, with police calls interspersed as required."

After one such refusal to renew , Commissioner Rutledge wryly asked: "Do we have to play a violin solo before we dispatch the police to catch a criminal?"

Another obstacle was funding. The city council was reluctant to expend public funds on an unproven endeavor. But an incident in March of 1922 removed opposition to the radio as a police tool. Police asked The Detroit News' fledgling radio station WWJ to broadcast the description of a missing boy. As a result of the broadcast the boy was quickly found safe in Ohio, buttressing the police department's argument before the city budget staff that money should be made available to continue radio experiments.

The experiment continued and was successful enough that in March of 1924 The Detroit News called in an editorial for more radio dispatched cars, noting : "The motor car has been a big asset to criminals, because it permitted a quick getaway. But the radio is swifter than any motor vehicle ever invented. By its use a well equipped police department can bar every city exit as soon as a description of the suspects can be obtained.... The police department now has three radio equipped flyers. It should have more. The motorized bandits would soon learn that Detroit had become a trap for them and they would move on to some town with less modern ideas."

By 1928 the radio-dispatched police car was a permanent fixture in the Detroit department. Two seven-passenger cars, referred to as "cruisers," were equipped with new radio receivers. Cruisers were heavy, high powered cars which carried a uniformed officer, two plainclothes officers and a man in charge, usually a detective or a patrol division sergeant. Each cruiser was armed with a riot gun and tear gas and equipped with a bullet-proof windshield. It did not take long for the successes of the radio experiment to be noticed. By the end of the year eight cruisers had been outfitted and were credited with making 551 arrests.

During 1929, the first full year of radio patrol operation, 22,598 police messages were broadcast, 2,228 of those were dispatched police runs. Radio equipped cars were credited with 1,325 arrests, with an average response time of 1 minute, 42 seconds, a decided improvement over the booth car system. By the end of 1930, 75 radio cars had been equipped and were credited with making more than 20,000 arrests.

But police calls were not the only use made of the police radio. The frequency that the police department used was a civilian radio band and was monitored like any other radio station. Beginning in 1932 during the Great Depression, when notified by the central employment agency of a job opening, the police dispatcher would broadcast the message to the unemployed eagerly listening in.

While one-way mobile radio communications was a dramatic improvement, it still had deficiencies. Officers had to stop at a phone or call-box to acknowledge a radio dispatch. They could not coordinate their activities with other police officers, as in the case of road blocks or while pursuing criminals. The officers were unable to request assistance, back-up, or notify others of crimes in progress.

It wasn't until 1933 when two-way radio communications were established, and this time it was another police department leading the way. The Bayonne, N.J., police department began using two-way radios in March, 1933, but the Detroit department was only a few months behind.

The growing recognition of the utility of two-way police radio communication was documented in 1934 by a Federal Radio Commission report. After one year's operation in 50 police departments it was reported that "one arrest resulted from every 10 calls; that in large cities, radio-dispatched police recovered $250,000 worth of stolen property every day; and that the average time to get the police to the scene of trouble was three minutes from receipt of a phone call."

Police Chiefs initially viewed motorized and radio-dispatched patrol as a panacea to all of their problems., allowing police to respond quicker and handle more calls with fewer officers. But the cost of such modernization was high. The closeness of the police to the community fostered through foot and bicycle patrol was eroded. As the police enclosed themselves inside the automobile alienation between police and the public began to surface. More time was being spent in the police car and less time was spent interacting with the public. The police car was becoing a major impediment to good community relations.

After decades of motorized policing in America, there is growing support among law enforcement leaders for a philosophy of "community oriented policing," removing some officers from the patrol car and placing them back on foot or on bicycles to reestablish contact with the citizens they protect and serve. In other words, "Back to the future."