Tales from the Crypt: The Wayne County Morgue

By Patricia Zacharias

Since the dawn of civilization, mankind has struggled to determine the causes of sudden, mysterious or violent deaths. The origins of forensic medicine -- the science of determining the causes, manner and circumstances of death -- can be traced to ancient Egypt around 3000 B.C. when King Zozer assigned a chief justice physician to investigate questionable deaths.

In ancient Rome, where the courts stressed the importance of medical legal experts, there were physicians who specialized in diagnosing the causes of unusual deaths.

When Julius Caesar was assassinated in 44 B.C. a physician concluded that only one of Caesar's 23 stab wounds was fatal. And when Emperor Nero had his mother secretly put to death for criticizing his mistress, he attended the autopsy to ensure authorities found the correct cause of her untimely passing. Or maybe not.

In Medieval times, English law decreed that a suicide victim's belongings and land be forfeited to the sovereign. Custom dictated the deceased be maligned and buried far beyond the walls of the Christian cemeteries.

The Church, not to be outdone, condemned the victim's soul to eternal damnation. These indignities and confiscation of the estate, could be avoided only if the coroner decided that the suicide stemmed from insanity or demonic possession. These early examinations and investigations though crude, spurred the development of forensic medicine

Autopsies fell out of favor with early Christians, disdained as a desecration of the corpse. The practice was prohibited by papal decree for nearly 800 years and was not revived until the 13th century.

In 1807, the University of Edinburgh in Scotland opened the world's first department of legal medicine. And later in the same century German pathologist Rudolf Virchow developed the microscope, advancing he science of forensic medicine.

In the United States in the early 1900s many cities adopted the British-style office of coroner, where physicians trained in forensic pathology replaced lay person investigators. New laboratories offered toxicology and histology testing.

In Michigan, state law requires that the Medical Examiner's Office must investigate all deaths that occur under unusual or suspicious circumstances.

By the 1920's, the population of Wayne County had swollen to more than a million, vastly outgrowing the tiny morgue in the basement of City Hall.

With only 20 vaults and 31 bodies on their hands, county coroners James Burgess and Jacomb W. Rothacher demanded the Board of County Auditors build a new facility. The doctors vowed that if they did not move swiftly, they would send bodies directly to the auditors' office.

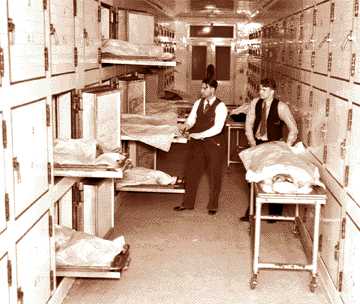

In 1926, the new Wayne County Morgue opened at the southeastern corner of Brush and Lafayette. The building, styled after an ancient Egyptian mausoleum, cost $300,000.

According to an old newspaper clip, the official name of the morgue was the Wayne County Coroner's Court and Mortuary. "The first floor houses the offices and crypt. The latter is finished in white tile and has space for 186 bodies and a viewing room. The second and top floor have two court rooms."

In 1928, Detroit Pastor William L. Stidger, in a Detroit News article headlined "Get Reservations Early if You Want to 'Sleep' in the Morgue," interviewed morgue employees who reported that during the previous year 3,000 bodies had passed through the portals of the building on Brush. Stidger asked "what kind of incident brings them here."

An unnamed attendant replied, "Last year 75 came in here as a result of falls, accident cases sent 167, automobiles 185, tuberculosis 511, heart diseases 497, railroad accidents 40, street car accidents 44, suicides 147, industrial accidents only 84, while there were 115 homicides. 43 of the homicides were in the months of July and August. When asked why so many murders in July and August the attendant responded, 'heat' then added with a smile, 'I guess they like this nice cool place in hot weather.'"

The morgue employee told of an old man who was brought in dead from a local bar.

"I investigated and found that he had five children. I called them all into the office and tried to get them to give their father a decent burial. They wouldn't do it. Not a single one of them. Judge Durfee says that a $100 funeral is enough for any man. He won't let us go any stronger than that as a rule. But the children wouldn't bury the old man.

"We decided to bury him at the expense of the county but on going through his clothes we found $800 sewed in the lining of his coat.

"Then all the kids wanted to claim his body and bury him. But we gave him a funeral here and if he could have awakened and seen that fine coffin we buried him in and the swell funeral we gave him with that $800 he would be smiling still."

The suicide rate soared during the Depression, increasing the workload of the Medical Examiner's office.

Over the years the Wayne County Medical Examiner's Office has pioneered and expanded investigative techniques and the scientific discipline.

In 1972, Dr Werner Spitz became Chief Medical Examiner and immediately instituted controversial reforms at the morgue. During his 16-year reign Spitz built an international reputation by testifying at high-profile trials and congressional investigations. He testified in investigations into the Mary Jo Kopechne drowning, the Oakland County child murders, the assassination of President John F. Kennedy and the Skid Row Murder trial in Los Angeles. He wrote a textbook that is a standard in medical schools around the world.

Dr. Spitz decreed that bodies were to remain in the facility no longer than 24 hours. He installed closed circuit television to ease the impact of identification on family members. He hired additional staff and trained them to run the morgue more efficiently. For the first time Wayne State University affiliated itself with the morgue. Dr. Spitz set up a private organization to help investigate Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS), commonly known as "crib death."

He began sending pituitary glands to outside firms for use in manufacturing Human Growth Hormone, a vital ingredient for children otherwise destined for dwarfism. He even took down the Morgue sign and replaced it with a more benign "Wayne County Medical Examiner" plaque.

Famed Los Angeles Medical Examiner Dr. Thomas Noguchi said of Spritz: "He's probably one of the best there is."

But like Noguchi, Spitz was less than deft at the politics that go with his office. Some of his changes came under attack and his caustic manner bred resentment among some of the staff.

In 1976, Spitz found himself the target of charges. Acting on tips from disgruntled staffers, the Wayne County Organized Crime task force accused Spitz of illegally using county time, money and equipment to benefit a private foundation; taking body parts from bodies without the permission of the next of kin; improperly conducting experiments to determine the effects of various bullets, and working at outside jobs, including the performing of autopsies for pay for Macomb County.

But Wayne County Prosecutor William Cahalan decided not to prosecute saying, "He was just being a doctor. I was convinced he was just doing what he thought was best for the medical world-which can sometimes be a lot different than what's best in the political world."

During the investigation, Spitz leveled charges against one of his assistants, Dr. Millard Bass. Acting on information from Spitz, investigators discovered a large cache of human bones and tissue hidden in several Greektown storage rooms rented by Bass. Bass eventually was charged with illegally beheading 11 bodies and stripping the flesh from 14 others.

The charges were later dropped when a Recorders Court judge later ruled that Bass was carrying on legitimate research. Bass had already resigned his county post and moved to the San Diego Zoo where, among other duties, he performed autopsies on dead animals. Bass sued Wayne County contending he had been wrongfully prosecuted and won a $1.8 million judgement, which was later reduced to $750,000.

After the court cases and media headlines, Spitz tried to keep a low profile. Nicknamed the "mean machine" by morgue employees, he continued his hectic workload. Spitz admitted to being addicted to his work. "I like the type of work I do, and I like the volume," he said. "People ask me how I can work with so much death. I guess you could say I was a doctor of death. But a dead body is just that, a dead body. It's a terminal product."

By 1988, Spitz tired of the fight over moonlighting and resigned. The news shocked the medical community. Dr. Robert Stein, chief of the Cook County medical examiner's office in Illinois, was critical of Wayne County, saying moonlighting was common among coroners and declaring that most of his colleagues "consider Werner Spitz to be the outstanding pathologist of this country, if not the world."

But according to Wayne County Executive Edward McNamara morale had perked since Spitz stepped down.

Dr. Bader Cassin replaced Spitz but his administration also proved controversial. By the early 90s the morgue was handling about 2,500 autopsies a year with only five pathologists -- more than twice the nationally recommended workload. Allegations of theft and vandalism of victims' property and charges of body hustling for local funeral homes made some wonder if the institution had deteriorated into a house of horrors.

Cassin came under fire for failing to renew his medical license and a Hamtramck widow sued Wayne County for taking her late husband's corneas without her permission.

In early 1995 the Wayne County Medical Examiner and staff moved into a new $14.5 million office near the Detroit Medical Center, with promises that its state-of-the- art design and equipment would remedy the problems the agency face in the building in Greektown.

Wayne County Executive Ed McNamara and current Medical Examiner Dr. Sawait Kanluen have vowed changes in hiring and training procedures and have promised to restore the once premier teaching institution to its former stature.