Detroit's Water Works Park a gateway to the past

By By Laurie J. Marzejka

In 1879 the City of Detroit built what was to become one of the wonders of the world on 110 acres of waterfront property -- the City Water Works. Better known as Water Works Park, the plant's 185-foot brick stand pipe tower became an instantly recognized Detroit landmark, gracing the backs of thousand of postcards and luring tourists from all over.

It was the place visitors never stopped talking about and the place you took your out-of-town relatives to see.

The main function of the site was to supply water to metropolitan Detroit, but the water commissioners had intended the grounds to be used as a public park as well. At one time, the park included a curving lagoon, where children could wade and navigate small sailboats, tennis courts, a baseball diamond, a picnic area, teeter-totters and swings.

In the middle 1870s, the City Water Works purchased the parcel of land, then well outside the city, from Peter Van Avery. Among the first structures erected were the stand-pipe tower and Pumping Station No. 1, the city's only pumping station until 1914.

Built in 1879, the station at its peak pumped 290 million gallons of water a day to thirsty Detroiters, but it was doomed by progress. The growing demands of the expanding city called for pumping stations to be placed throughout the area in order to maintain water pressure. The pumping station was not high on the list of tourist attractions, but the stand-pipe tower was an instant hit.

Once called "an architectural exclamation point," this slender minaret-like tower was built to provide an equal pressure for water being pumped into Detroit's water mains. Standing 185 feet tall, this brick structure covered an iron stairway that circled the stand-pipe up the middle that was the business part of the tower.

Climbing up the 202 winding steps of this stairway, one was given increasingly exalted views of the park below from the narrow windows in the brick structure. From a balcony at the top, one could see downtown Detroit. Children and adults alike enjoyed the challenges and rewards of climbing this stairway.

In a letter to The Detroit News Town Talk editor George W. Stark, published March 11, 1945, William R. Carnegie of Grosse Pointe Park recalls his adventures with the tower:

"I address you as the protector and defender of the things that had to do with Detroit when the city could rightfully claim to be Detroit the Beautiful ... I made the acquaintance of the tower in the early days of its career. It had been up only 11 years when fate assigned me the task of seeing that the water did not freeze in the pipe and interfere with its use as a safety valve for the water mains.

"The architect hadn't thought of that and made no provision for heating the tower. A coal-burning stove was installed, but, as there was no chimney, the gas fumes had to find their way up the staircase and vents wherever they could find them. So, filling my lungs with good fresh air, I would dash up the spiral stairs as fast as I could, make sure that the pipe was free of ice and then get down as quickly as I could to avoid asphyxiation."

No one knows the cost of building this tower, but it won praise and honors as a splendid example of its type of architecture.

Council President John C. Lodge said, "It was the Empire State Building of its day..."

Its usefulness ended in1893 as new pumping stations came on line to keep up water pressure. But it stayed on as a tourist attraction until being found unsafe and unrepairable in 1945. City Council approved a $17,000 appropriation to have the tower razed. The tower was eventually replaced as the top postcard attraction by the park's eight-foot high floral clock.

The first superintendent of grounds at Water Works Park and the inventor of the floral clock was Elbridge A. "Scrib" Scribner. Scrib was a man of great skill and imagination. He built a small greenhouse in the park and began to grow his own plants and flowers. In 1893, he began work on the clock, designing an intricate water-driven system using cup-shaped paddle wheels to run the mechanism.

He consulted with a Detroit jeweler and watchmaker named Fisher and worked out the gearing ratios: The clock kept accurate time.

The mechanism was placed on an 8-foot-high knoll just inside an entrance to the park. Flowers and greens were planted to form its face, and bordering edges, and its wood hands were festooned with flowers. In 1921, the clock was fenced in to deter children from swinging on the hands of this hillside wonder.

In 1934, the Water Board decided that waning public interest did not justify the cost of maintenance and repair. Destined for the junk heap, the floral clock was saved by Henry Ford, who had a tender regard for tokens of an older time and who had tinkered with timepieces in his youth.

Ford arranged to have the clock and the soil in which it rested removed to Greenfield Village, where it was restored - although the old water-driven mechanism was converted to run on electricity. It remained at Greenfield Village until sometime in the late 1980s.

The floral clock was not the only contribution Scribner made to Water Works Park. He also designed a floral cow in a field of corn; a floral tepee with smoke curling from the top; a calendar made entirely from plants and arranged so that he could change the date daily merely by transfering a few blooms and a tribute to members of the board of park commissioners spelling out their names in flowers.

The funds that made Scrib's labors of love possible came from a bequest of $250,000 from the estate of Chauncy Hurlbut, who for many years served as president of the Board of Water Commissioners. Hurlbut spent the last 11 years of his life improving the water works system and left almost all of his estate for maintenance of the grounds.

In 1895, funds were used from this bequest to erect a stone entrance to the park known as the Hurlbut Memorial Gate.

Detroit retains no greater monument to the passion for embellishment that characterized the Victorian Era. This huge gateway, 132 feet wide by 50 feet high, is adorned with scrolls and figures and has a dual stairway leading to a terrace 12 feet above ground. A stone eagle, with wings outspread, occupies the crest at its dome. A granite bust of the monument's namesake, stolen in 1974, had a place of honor below the eagle. Throughout the years, this monument has suffered from vandalism and neglect. A 1990 engineering study found it was in danger of collapse if not repaired soon.

Concern for the demise of this historical monument spurred civic leaders to take action. Tom Schoenith, owner of the Roostertail, spearheaded his business colleagues in the EastBank Association to start a long-term fund-raising drive to save and restore the Hurlbut Memorial Gate. The kick-off of this drive was an auction held at the Roostertail in 1992.

"To have one of the very few monuments left in Detroit falling apart is something I can't live with," Schoenith said. " I love the history of Detroit."

In 1912, the name of the park was officially changed to Gladwin Park, to honor Maj. Henry Gladwin, British commander of Fort Detroit during the siege of Ottawa Chief Pontiac in 1763. The new name appeared on official papers and many of the postcards, but Detroiters continued to call it Water Works Park.

Concern for the safety of the city's water supply forced closure of the park during World War I. It was off limits again at the start of World War II and did not reopen until V-J Day, Aug. 15, 1945.

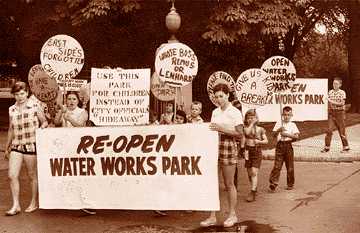

The biggest blow of all came in 1951, when the entire site was closed. It took six years of public protest to get back seven acres of the original 110-acre park. This was a section along the waterfront used mostly by fishermen. Another six acres, fronting on Jefferson, was reopened to public use in 1961, the year operations of Pumping Station No. 1 ceased. for good. This area was used as a playfield and was accessed by entering through the Hurlbut Memorial Gate.

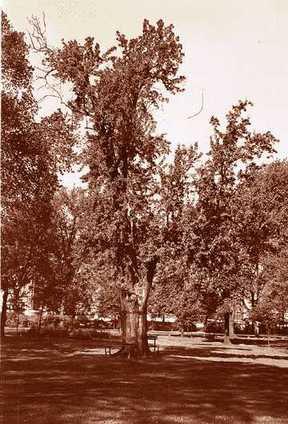

There are legends concerning 12 French mission pear trees that were planted on these grounds before it was Water Works Park. The legends include tales of unrequited love and miserly in--laws. The trees were named the "Twelve Apostles."

For years, every farm fronting on the Detroit River had a cluster of pear trees descended from the Apostles and many stood in front of residences along Woodward and Jefferson.

No one has been able to determine when the Twelve Apostles were first planted or where they came from. Water Works Park did contain one last survivor of the Apostles, and there was even some debate as to which one remained -- Peter or Judas. This last survivor lived for more than two centuries and grew to more than four feet in diameter. All attempts to save it failed.

Today, if you drive down Jefferson to Cadillac, you can still see the Hurlbut Memorial Gate, although it's now nothing more than a gateway to the past. It leads to a fenced-off plot of land marked "no trespassing."