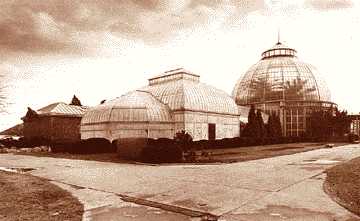

The orchids that saved the Belle Isle Conservatory

By Vivian M. Baulch

The Belle Isle Conservatory was designed and built at the turn of the century, but by the middle of the century it had fallen into serious disrepair. Portions of the old domed structure had been closed shortly after World War II when they were deemed unsafe.

But then came Mrs. Edgar Whitcomb and her orchids.

In the 1930s devoted orchid growers could count on no more than five percent success in getting seeds to germinate. A Michigan gardener who wished to breed these rare exotic flowers required inexhaustible patience.

William Crichton was just such a devoted gardener. He had been Mrs. Whitcomb's head gardener for 27 years at her Grosse Pointe estate, and had been patiently nurturing a garden of treasured orchids for all those years. The orchids would be displayed for a few days annually at the Belle Isle Conservatory and at the Detroit Flower Show, thrilling thousands of orchid lovers.

Anna Scripps, the daughter of The Detroit News founder James E. Scripps, had married Edgar B. Whitcomb, a longtime director of the Detroit News. She loved flowers, especially orchids, which filled two greenhouses at her Lake Shore Drive home. The flowers had been displayed every year at the Detroit Flower show since 1927. A staff of gardeners maintained the difficult blooms under Crichton's direction.

When she died in 1953 she left the entire collection of more than 600 plants to the Belle Isle Conservatory. The gift included cymbidiums, dendrobiums, oncidiums, vandas, epidendrums, cypripediums, phalaenopsis, odontoglossums, catteyas and others of equally difficult spellings.

The prize orchids had been carefully raised from seed imported from all parts of the world. In 1940 she acquired 25 hybrid cypripediums from England to save them from the war. Her efforts earned praise and awards from flower lovers and horticultural groups.

On April 6, 1955, a grateful City of Detroit announced that the old domed conservatory would be renamed the Anna Scripps Whitcomb Conservatory and rebuilt at a cost of $450,000. All the old wood beams in the glass-domed structure, which had been decaying for 50 years in the moist atmosphere, were replaced by aluminum ones.

New rock work was installed and large palm trees were planted in the main 85 foot high dome. Other rooms were remodeled to house the orchids, the cacti exhibit, the fernery and exhibition sections.

The exhibition section changed displays with each season and featured a moss-covered short tunnel from the adjoining aquarium. The dark dank area had a small waterfall on one side that was a favorite with children who usually came dressed in their Sunday finery to pose for family photos.

The following is from a March 26, 1939 article on the Whitcomb orchids in The Detroit News Rotogravure Section:

Thrilling as a jungle movie: growing orchids in Detroit!

Of the throngs who will stand this week, before the orchid collection, which has become an annual attraction at the Michigan Flower and Garden Exhibition, only a few, perhaps will know that these exotic blooms are Michigan born and bred.

Every year, from the private grteenhouse of Mrs. Edgar B. Whitcomb in Grosse Pointe, a collection of Cattleyas, Phalaenopsis, Cymbidium, Cypripedium and other species is entered at the Detroit show. They are displayed in a pyramid of airy forms, like a flock of delicately tinted butterflies.

Evocative of wild and distant scenes, of thrilling chapters in the life of some dauntless plant explorer among the forests of Brazil, in sober fact, the orchids at the spring Flower Show have never traveled farther than to Convention Hall. They have made no perilous journey over mountain and sea. They have merely been driven down to the exhibition prosaically in a truck.

Nevertheless, their story, told by the skilled orchid breeder who grows these lovely tropicals in a Detroit glasshouse, surpasses any jungle movie in excitement. The life story of a Michigan orchid moves from thrill to thrill, along a trail beset with dangers and fraught with hair-breadth escapes. To grow orchids in Grosse Pointe is no less adventurous than to gather them in Hatagama.

Some 10 years ago, William Crichton, head gardener on the Whitcomb estate, began his search down the warm and humid aisles of a bloom-filled greenhouse in preparation for the show, this week. He had to choose the parents of the orchids to be exhibited 10 years later, those on view today.

With a fine brush, Crichton transferred the pollen of one gorgeous flower to another. The seed pod of the fertilized flower would contain a quarter million seeds, a few hundred thousand of which would be planted and half of them would bloom nine years after spring.

Because the modern orchid grower studies the ancestry of his plants, he can be sure, Crichton says, that a large percentage of his seeds will produce fine flowers. He can predict their possible forms and colorings and qualities. But exactly what will happen, he must wait nine years to learn.

Until recently the orchid breeder could count upon no more than five percent of selected seeds surviving to germinate. Now the famous Cornell University method had raised the life expectancy of orchid seeds to 50 per cent. By this method seeds are sown in a propagating jelly, which looks like library paste. It is composed of chemicals, salts and nutrients made from seaweed.

Though in a large, commercial house, the breeder will make a dozen or more crossings, pollinating millions of seeds, Crichton will cross but one, possibly two, pair each year. He will save perhaps 10,000 to 20,000 seeds and plant half of them. Perhaps among the seeds he does not plant is one that would produce the supreme hybrid, the orchid of orchids, but that is a chance he has to take. After all, five flasks filled with the Cornell agar jelly will be sufficient to fill a small orchid house with bloom.

Each flask, holding from 500 to 1,000 seeds, fine as star dust, is corked with cotton and covered with a glass.

In 10 months flecks of green appear on the thick, white gelatine within the flask. Minute seedlings are ready for the outside world, where, for eight or nine years more, they must face the hazards of life. Drafts, germs, insects, diseases, changes in temperature, careless hands would destroy them.

Little pots filled with a special orchid moss, known as Osmunda fiber, are prepared, perhaps 10 or a dozen, for the benches of the private orchid house. The grower transfers the bits of green, washing off the jelly, scattering the thousands of seedlings, like chopped parsley, over the smooth, spongy surface of the moss.

Years pass. The infant plants are moved from the nursery to less crowded quarters. Weak individuals are discarded. Finally, each survivor stands alone in a pot, guarded, sprayed, scrubbed with soap, watered and fed, by day and by night, in controlled degrees of heat and humidity.

Thus, from a quarter of a million seeds pollinated in 1929, from 5000 sown, 2500 germinated, 1200--all choice--potted, he may consider 10 outstanding.

Last fall one orchid flowered that will be treasured for its surpassing loveliness.

Today, thousands of spectators will pause before the orchids at the Flower Show. Young men, noting the eager light in the eyes of the girl beside them, will jingle their keyrings and wonder how many luncheons they could do without to afford and orchid on their budget. Nothing, to the feminine taste, wears like an orchid."

The Michigan orchids at the Flower Show, like the blooms produced in the great commercial nurseries where orchid-breeding in Big Business, are, for all their exotic charm, generation removed from the first gorgeous beauties Capt. Cattley risked his life to bring from the jungles.

Still, to the thrilled gaze of thousands, this week, orchids remain the symbol of glamor, of romantic loveliness."