Research

The boreal toad is an endangered species in the state of Colorado and is just one of many amphibians whose numbers are dramatically declining. This alarming trend prompts many questions and actions.

The boreal toad is an endangered species in the state of Colorado and is just one of many amphibians whose numbers are dramatically declining. This alarming trend prompts many questions and actions.

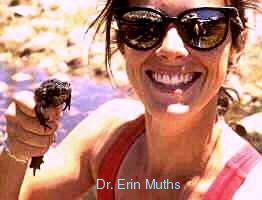

The high mountains of Colorado are known for their world class downhill skiing. Because of their popularity, downhill ski resorts in Colorado are under pressure to keep growing ... better ski runs, newer condominiums, more convenient shopping, etc. What impact development will have on the boreal toad'srecovery is not fully known. So far, developers give a 100 foot easement surrounding a pond or lake where toads have been found. But now researchers are asking how much habitat do toads really need? According to Dr. Erin Muths, "We really don't know." There is no baseline information on habitat needs of toads so we can only estimate how much land is needed. Research has to provide the needed information.

The high mountains of Colorado are known for their world class downhill skiing. Because of their popularity, downhill ski resorts in Colorado are under pressure to keep growing ... better ski runs, newer condominiums, more convenient shopping, etc. What impact development will have on the boreal toad'srecovery is not fully known. So far, developers give a 100 foot easement surrounding a pond or lake where toads have been found. But now researchers are asking how much habitat do toads really need? According to Dr. Erin Muths, "We really don't know." There is no baseline information on habitat needs of toads so we can only estimate how much land is needed. Research has to provide the needed information.

According to Dr. Muths,it will take 5 or more years of field work. Following the field work, there is a good deal of time to be put into the data analysis and writing before finally submitting a manuscript to be published. It will take at least seven years to get the information published that will document the specific needs of toads so their habitat can be adequately protected.

According to Dr. Muths,it will take 5 or more years of field work. Following the field work, there is a good deal of time to be put into the data analysis and writing before finally submitting a manuscript to be published. It will take at least seven years to get the information published that will document the specific needs of toads so their habitat can be adequately protected.

One study (designed and begun by Dr. Stephen Corn and now continued by Dr. Muths) is in Rocky Mountain National Park.The lakes where Dr. Muths is now conducting research are high mountain lakes, seemingly pristine, but even populations there are declining.

Field Research

Past research verifies that toads use water for breeding and early stages of metamorphosis, but how far do they travel away from their high ponds or lakes after breeding, when they don't breed at all, or when they are in their hibernation burrows?

Through the use of PIT tags and radio telemetry (methods for tracking individuals), these questions are beginning to be answered.

Identifying Individual Toads

PIT tags are very small tags used for identifying individual toads. The pit tags are the shape of pencil lead and about 1/2 inch (2 cm) long. The tags are inse rted just under the skin on the toad's back, alongside of the backbone.

rted just under the skin on the toad's back, alongside of the backbone.

Each tag has a unique number. A hand-held scanner is used to pick up the identifying number from the PIT tag.

A researcher rolls the scanner over the back of a toad and then records an identifying number. Sometimes it takes several passes before the numbers register. This is similar to the technology used by cashiers at modern stores when scanning merchandise for prices. The PIT tag identifies the individual, but how do researchers find the toads?

Finding Individuals

Researchers are also using tiny radio transmitters ("radios") that are slipped around the waist of a toad. The tiny radios weigh only 2 grams.

The radio transmits a unique signal that is picked up by a hand held antennae. The signal (a beeping sound) becomes louder as the researchers get closer and closer to the toad.

Collecting Data

When they find a toad they record these facts

1. Where is it sitting?

2. Which direction is it facing?

3. What is the type of cover (vegetation)?

4. Is it in a burrow?

5. Is it in water?

6. What is the soil moisture?

The researcher marks the location of the toad in a 1X1 meter (39.3 inch) plot, then describes the basic ground cover consisting of forbs (plants other than grasses), grasses, and shrubs found in the plot. The biologist also identifies vegetation on 5m transects in each cardinal direction (N,S,E,W) from the location of the toad. Then he or she enters the information in their field notebook or laptop.

At this point the biologist will pick up the toad and scan it for an identification number. If the toad already has a PIT tag, the identification number is recorded with data. Throughout the field season, when the biologist finds a toad without a PIT tag, he or she will insert a tag just below the skin on the toad's back.