The Slovak national movement

At the end of the 18th century the Habsburgs rejected the Enlightenment and reforms. The radicalism of the French revolution, which found support especially in the secret and unsuccessful movement of the Hungarian Jacobins, indirectly contributed to this. This organisation prepared an armed uprising against the Habsburgs and planned to create a democratic and federative republic in Hungary, composed of four autonomous national provinces, including the Slovak province. However, its leaders were arrested and executed in Buda in 1795.

The Napoleonic wars left Slovakia untouched. Only Bratislava was involved as the location of the signing of the peace treaty in 1805 after the battle near Slavkov (Austerlitz). The wars only multiplied the conservatism of the Habsburg court and Hungarian aristocracy. However prudent absolutism did not manage to suppress the vitality of the national movements and liberal ideas.

The formation of modern nations in Central Europe was accelerated during the reign of Joseph II at the end of the 18th century. Slovak scholars, in reaction to the frequent claims of Hungarian intellectuals that Slovaks were only a subjugated people and that Magyars were the lords in Hungary, emphasising that Hungary was the mother land of equal nations. They defended the equality of people and nations, and through education they tried to improve the weak position of farmers. They worked on the cultivation of their own language and they placed emphasis on autochthony and the role of Great Moravia in the history of Slovaks. In 1783 the first Slovak newspaper, Prešpurské noviny (Pressburg Newspaper) was published in Bratislava, and the first educational and scholarly associations and public libraries were established soon after. However, the dualism on which two images of the character of Slovaks was based made the forming of a modern Slovak nation more difficult. The Catholic majority of scholars proclaimed their national independence and, thanks to the circle of Anton Bernolák, codified the Slovak standard language (Bernolákovčina). In 1792 they established the Slovak Scholarly Society (Slovenské učené tovarišstvo) in Trnava. It had 500 members and was the largest cultural society in Hungary at that time. Meanwhile the evangelical minority considered their religious language – the Czech language – as the standard language of the Slovaks and saw the Slovak people as part of the Czechoslovak tribe.

The formation of modern nations in Central Europe was accelerated during the reign of Joseph II at the end of the 18th century. Slovak scholars, in reaction to the frequent claims of Hungarian intellectuals that Slovaks were only a subjugated people and that Magyars were the lords in Hungary, emphasising that Hungary was the mother land of equal nations. They defended the equality of people and nations, and through education they tried to improve the weak position of farmers. They worked on the cultivation of their own language and they placed emphasis on autochthony and the role of Great Moravia in the history of Slovaks. In 1783 the first Slovak newspaper, Prešpurské noviny (Pressburg Newspaper) was published in Bratislava, and the first educational and scholarly associations and public libraries were established soon after. However, the dualism on which two images of the character of Slovaks was based made the forming of a modern Slovak nation more difficult. The Catholic majority of scholars proclaimed their national independence and, thanks to the circle of Anton Bernolák, codified the Slovak standard language (Bernolákovčina). In 1792 they established the Slovak Scholarly Society (Slovenské učené tovarišstvo) in Trnava. It had 500 members and was the largest cultural society in Hungary at that time. Meanwhile the evangelical minority considered their religious language – the Czech language – as the standard language of the Slovaks and saw the Slovak people as part of the Czechoslovak tribe.

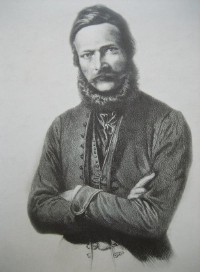

In the first half of the 19th century, the peaceful co-existence of the nations of Hungary became increasingly complicated. The Hungarian Parliament and the aristocratic sees supported the Hungarian culture and language, and the Hungarian language became the official language of the country. In the 1840s, the reform politicians surrounding Lajos Kossuth wanted to transform multi-ethnic Hungary into a Magyar national state. The aristocracy and some rich and educated sectors of society were Magyarised, while the intelligentsia in particular defended and cultivated the Slovak national idea. Slavic mutuality, which thanks to Jozef Kollár and Pavol Jozef Šafárik called for the cultural co-operation and unity of Slavs, was considered a significant instrument of protection against assimilation. Slavic folk culture, as the most individual sign of national identity, also began to be emphasised. However only the younger generation of scholars – the followers of Ľudovít Štúr (1815-1856) – managed to bring together differing views on nationality and language. In 1843 they elaborated a new standard language which was adopted by both streams of the national movement. This strengthened the feeling of national independence and unity among Slovaks.

The European-educated followers of Štúr tried to raise the quality of national and public life through a wide variety of activities. Several cultural and economic societies were established aimed at the lower middle classes, and the first political newspaper was published in Bratislava. A Slovak political programme was formed around Ľudovít Štúr; it called for the modernisation of Hungary, abolition of serfdom, equality of people before the law, civil rights in general and language rights for the Slovaks. Štúr presented it to the Hungarian Parliament in late 1847 and early 1848, thus becoming the first representative of the national rights of Slovaks.

The European-educated followers of Štúr tried to raise the quality of national and public life through a wide variety of activities. Several cultural and economic societies were established aimed at the lower middle classes, and the first political newspaper was published in Bratislava. A Slovak political programme was formed around Ľudovít Štúr; it called for the modernisation of Hungary, abolition of serfdom, equality of people before the law, civil rights in general and language rights for the Slovaks. Štúr presented it to the Hungarian Parliament in late 1847 and early 1848, thus becoming the first representative of the national rights of Slovaks.

Revolutionary changes were imminent. In March 1848 the Hungarian Parliament abolished serfdom, began to tax the aristocracy and anchored the equality of people in law. The Hungarian government was created and the independence of Hungary was strengthened. The Slovak national movement welcomed these changes, but they also called for the abolition of serfdom and universal suffrage. Being inspired by other national movements, in May 1848 they publicly called for the autonomous separation of Slovakia within the framework of Hungary. These national issues in Central Europe became the main source of tragic conflicts in the two-year revolutionary period.

Since the Hungarian government persecuted the Slovak activists and ignored their programme, they also became the allies of imperial Vienna. The Slovak National Party, the very first Slovak political organ, was established in Vienna, and in 1849, with the help of Slovak volunteers fighting side by side with the imperial army, they were unsuccessful in their attempt to separate Slovakia from Hungary and establish a Slovak crown country, which was to be subordinate to the imperial institutions in Vienna. Although the movement failed, its ideas were carried forward into the 1860s when a Slovak national movement was successfully developed. In 1861 a total of 5,000 people in Martin adopted the Memorandum which called for the promotion of Slovakia to an autonomous formation within the framework of Hungary (the Upper-Hungarian Slovak Surroundings). In 1863 the emperor recognised the cultural institution Matica slovenská, which became a symbol for the Slovaks. Furthermore, three Slovak church gymnasiums were established, and Slovak press and associations developed. The national movement had managed to reach the general public.

However the situation changed swiftly after the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867. The national law which was to guarantee the language rights of non-Magyars was ignored by Hungarian authorities and governments. Fifty years of strong national oppression began. There were no Slovak secondary schools, elementary schools and the names of municipalities were Magyarised, and Matica slovenská, Martin was banned. Slovak activities were maliciously labelled as ‘pan-Slavism’ and their participants were frequently discriminated against and imprisoned. A shooting into a crowd of religious followers in Černová near Ružomberok (1907) resulted in the deaths of 15 people, symbolising the arrogance of power.

However the situation changed swiftly after the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867. The national law which was to guarantee the language rights of non-Magyars was ignored by Hungarian authorities and governments. Fifty years of strong national oppression began. There were no Slovak secondary schools, elementary schools and the names of municipalities were Magyarised, and Matica slovenská, Martin was banned. Slovak activities were maliciously labelled as ‘pan-Slavism’ and their participants were frequently discriminated against and imprisoned. A shooting into a crowd of religious followers in Černová near Ružomberok (1907) resulted in the deaths of 15 people, symbolising the arrogance of power.

After 1867, the social structure of Slovak society was distorted because the wealthier layers of society became estranged. The education level of Slovaks stagnated; their culture developed only modestly. The small town of Martin became the main centre of national life. In politics, represented by the Slovak National Party, and in culture, there was an emphasis upon plebeian features and passivity, vigilance against modernisation and hope for liberation by Russia.

The national movement began to take a more active role only in the last decade of the 19th century. The Slovak industrial and financial capital gradually grew, Slovak-Czech relations became more intense and an adequate political spectrum for the period was formed – national conservatives, members of the Catholic people’s party, agrarians, liberals, social democrats. All streams called for the legalisation of general suffrage, adherence to the national law and solutions to the social problems of farmers and workers.