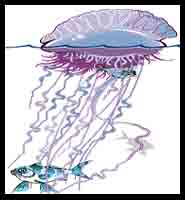

Portuguese Man-of-War

Portuguese Man-of-War

(Bluebottle - Physalia spp. - Hydroid)

"`Ili Mane`o, Pa`imalau, Palalia or Pololia"

Family: Physaliidae, Order: Siphonophora, Class: Hydrozoa, Phylum: Cnidaria

|

| INJURY MECHANISM | Long blue, threadlike tentacles. | |||

| SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS | Stinging, burning, redness, swelling of lymph nodes. Long welt lines. Severe reactions: difficulty with breathing and cardiac arrest. | |||

IMMEDIATE FIRST AID ADVICE: 1. Rinse the area liberally with seawater or fresh water to remove any tentacles stuck to the skin. This can be from a spray bottle or in a beach shower. Do not apply vinegar. A study shows that vinegar in these stings sometimes makes the sting worse. (Portuguese man-of-wars belong to a different family than box jellyfish [Carybdea alata] and therefore must be treated separately.) | ||||

| COMMON HABITAT | Open ocean. Bays and beaches during strong onshore winds. | |||

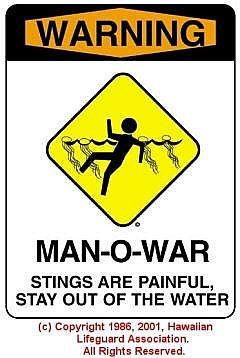

| PREVENTION | Avoid areas where they frequent. Usually found when winds blow in from the ocean onto land. Observe posted signs. | |||

The portuguese man-of-war "jellyfish" - in Hawaiian, `Ili Mane`o, Pa`imalau, Palalia or Pololia - is actually any of various invertebrate, jelly-like marine animals of the family: Physaliidae, order: Siphonophora, class: Hydrozoa, and Phylum: Cnidaria. These pelagic colonial hydroids or hydrozoans are infamous for their very painful, powerful sting and are very common in Hawaiian ocean waters.

The portuguese man-of-war "jellyfish" - in Hawaiian, `Ili Mane`o, Pa`imalau, Palalia or Pololia - is actually any of various invertebrate, jelly-like marine animals of the family: Physaliidae, order: Siphonophora, class: Hydrozoa, and Phylum: Cnidaria. These pelagic colonial hydroids or hydrozoans are infamous for their very painful, powerful sting and are very common in Hawaiian ocean waters.

The man-of-war ranges or occurs most commonly in the tropical and subtropical regions of the Pacific and Indian oceans, and the northern Atlantic Gulf Stream, although found in warm seas throughout the world. It is sometimes found floating - some even say "swarming" - in groups of thousands. Physalia physalis is the only widely distributed species. P. utriculus, commonly known as the bluebottle, frequently occurs in Hawai`i, in the Pacific and Indian oceans.

The Australian Museum notes on its luminous web page, that the portuguese man-of-war ". . . is not a single animal but a colony of four kinds of highly modified individuals [polyps]. The polyps are dependent on one another for survival." Click here or on this image for a diagram of the different types of descending polyps.

The man-of-war's body consists of a gas-filled (mostly nitrogen), bladder-like float (a polyp, the pneumatophore) - a translucent structure tinted pink, blue, or violet - which may be 3 to 12 inches (9 to 30 centimeters) long and may extend as much as 6 inches (15 centimeters) above the water. Beneath the float are clusters of polyps, from which hang tentacles of up to 165 feet (about 50 meters) in length. The polyps are of three types: dactylozooid, gonozooid, and gastrozooid, concerned, respectively, with detecting and capturing prey, with reproducing, and with feeding. The "animal" moves by means of its crest, which functions as a sail.

Initially, Physalia reproduce sexually - the sperm of one mature colonial hydroid fertilizes the egg of another reproducing a larva. Then like other invertebrates and hydroids, larval Physalia reproduces itself by mitotic, asexual reproduction to yield or bud, i.e., grow, genetically identical colonial offspring within and onto itself. (The mitotic process involves the facilitation of the equal partitioning of replicated chromosomes into two identical groups.) Asexual reproduction leads to a rapid growth; sexual reproduction produces genetic differentiation, combined both lead to rapid increase in species numbers. The biomass increases or "grows" opportunistically from both reproductive processes in favorable conditions: adequate food supply, equable, suitable temperature, and adequate ranging territory or space to live. It is no wonder that there is a thriving, proliferation of Physalia spp. in Hawaii's temperate, food rich, expansive ocean waters.

Tentacles of the dactylozooids bear stinging nematocystic (coiled thread-like) structures that paralyze small fish and other prey. The gastrozooids then attach to the immobilized victim, spread over it, digesting it. The Portuguese man-of-war is eaten by other animals, including the loggerhead turtle, Caretta caretta. The small fish, Nomeus gronovii, lives among the tentacles of Physalia and is nearly immune to the poison from the stinging cells. Nomeus feeds on the tentacles, which are constantly regenerated; sometimes the fish is eaten by Physalia. Clown or Clown Anemone fish (Amphiprion spp.) and the Yellow-jack fish (Caranx bartholomaei) reportedly have a similar commensal symbiotic relationship, i.e., a mutually beneficial relationship with no negative or pathogenic effect on the host or symbiont.

Reportedly, another interesting food chain manifestation occurs occasionally. When leatherback sea turtles (Dermochelys coriacea) feed on man-of-wars, like jellyfish - their favorite foods, sharks are attracted to and feed on the sea turtles, and, may be attracted to and try to feed on things that look like sea turtles, e.g., humans swimming in murky waters, on surf boards, etc.

The portuguese man-of-war itself will eat basically anything that comes in contact with its stinging tentacle polyps, the dactylozooids. As Physalia drifts down wind, the long tentacles "fish" continuously through the water. Muscles in each tentacle contract and drag prey into range of the digestive polyps, the gastrozooids, which, acting like small mouths, consume and digest the food by phagocytosis - by secreting a full range of enzymes that variously break down proteins, carbohydrates and fats. The prey consists mostly of small crustaceans, small fish, algae and other members of the surface plankton which the man-of-war ensnares in its entangling, stinging nematocystic threads.

The sting of Physalia is very painful to man and can cause serious effects, including fever, shock, and interference with heart and lung action. When stung, carefully, pick or brush off any visible tentacles - try not to use your fingers - use your towel, fins, etc. Rinse with fresh or salt water - do not use vinegar. For severe pain, try applying heat or cold, whichever feels better to the victim. Immediate medical attention may be required as their stinging may bring about anaphylactic shock. (Read detailed first-aid information just below.)

The nematocystic sting toxin secreted from the tentacles of the dactylozooids, a mixture of enzymes, is a neurotoxin about seventy-five percent as powerful as cobra venom. The toxins contain a complex mixture of polypeptides and proteins including catecholamines, histamine, hyaluronidase, fibolysins, kinins, phospholipases and various hemolytic, cardiotoxic and dermatonecrotic toxins.

The most common result of contact with the man-of-war - the residual whip-like, red wavy, stringy welts on the skin from contact with the blue tentacle - is a painful papular-urticarial eruption. The lesions can last for minutes to hours, and the rash may progress to urticaria, hemorrhage, or ulceration. Recurrent episodes of urticaria may last four to six weeks at the site of envenomation. (The pathophysiology of sting induced urticaria is that it occurs following release of histamine, bradykinin, kallikrein or acetylcholine resulting in intradermal edema from capillary and venous vasodilation and occasional leukocyte infiltration.)

The following is from one of our All Stings Considered web pages and is excerpted from the book, All Stings Considered - First Aid and Medical Treatment of Hawai`i's Marine Injuries by Craig Thomas, M.D. and Susan Scott (University of Hawaii Press, 1997):

| First Aid for PORTUGUESE MAN-OF-WAR STINGS: |

For the average Hawaii Portuguese man-of-war sting:

Although formerly considered effective, vinegar is no longer recommended for Portuguese man-of-war stings. In a laboratory experiment, vinegar dousing caused discharge of nematocysts from the larger (P. physalis) man-of-war species. The effect of vinegar on the nematocysts of the smaller species (which has less severe stings) is mixed: vinegar inhibited some, discharged others. No studies support applying heat to Portuguese man-of-war stings. Studies on the effectiveness of meat tenderizer, baking soda, papain, or commercial sprays (containing aluminum sulfate and detergents) on nematocyst stings have been contradictory. It's possible these substances cause further damage. In one U.S. Portuguese man-of-war fatality, lifeguards sprayed papain solution immediately on the victim's sting. Within minutes, the woman was comatose, and later died. Alcohol and human urine may be harmful on Portuguese man-of-war stings. An Australian study reports that both alcohol and urine caused massive nematocyst discharge in the box jellyfish, Chironex fleckeri. Most Hawaii Portuguese man-of-war stings disappear by themselves, sometimes within 15 or 20 minutes. Because of this, even harmful therapies often appear to work. A key concept in the first aid of any injury is: Do no harm. Therefore, avoid applying unproven, possibly harmful substances on stings. See a doctor if pain persists, the rash worsens, a feeling of overall illness develops, a red streak develops between swollen lymph nodes and the sting, or if either area becomes red, warm and tender. (See Staph, Strep and General Wound Care for signs of infection.) Few Portuguese man-of-war stings in Hawaii cause life-threatening reactions, but this is always a possibility. Some people are extremely sensitive to the venom; a few have allergic reactions. Consider even the slightest breathing difficulty, or altered level of consciousness, a medical emergency. Call for help and use automatic epinephrine injector if available. |

The beaches on Oahu's East shore, commonly referred to as the Windward coast, are infamous for the presence of the portuguese man-of-war. This is as there is a nearly constant inshore wind blowing.

The beaches on Oahu's East shore, commonly referred to as the Windward coast, are infamous for the presence of the portuguese man-of-war. This is as there is a nearly constant inshore wind blowing.

We routinely notify the media when we anticipate or observe large "swarms" - the press has been very cooperative in airing and printing these warning and alert notices. Guarded beaches on O`ahu are posted with special signs by lifeguards when there are portuguese man-of-wars or jellyfish swarming in the surrounding ocean. Observe these signs, stay out of the water, to avoid being stung - a very painful, perhaps even potentially deadly experience.

Don't touch this animal, especially its tentacles - even when Physalia is beached and dead. Research has shown that the toxin of the nematocysts remains potent for an extended period of time - even several hours. Curious keiki (children) will want to play and poke them - keep children far away from these potentially, excruciatingly painful creatures.

Don't touch this animal, especially its tentacles - even when Physalia is beached and dead. Research has shown that the toxin of the nematocysts remains potent for an extended period of time - even several hours. Curious keiki (children) will want to play and poke them - keep children far away from these potentially, excruciatingly painful creatures.

If you are stung at a guarded beach see the lifeguards on duty. They can render minor first-aid, or, for more serious cases, call and radio for emergency ambulance or MEDEVAC (helicopter medical evacuation) assistance.

Box jellyfish, Carybdea alata and Carybdea rastonii, also regularly "swarm" to Hawaii's Leeward (West and South) shores nine to ten days after the full moon. Be well forewarned; observe posted special warning signs and be attentive to media warning and alert announcements.

Links We Like: Emedicine.com has a thorough monograph, web page on Coelenterate and Jellyfish Envenomations that's worth a visit - if you're so inclined, please click here to go there. Be sure to read Dr. Carol Hopper's marine life profile of Physalia spp. and other interesting sea creatures at the Waikiki Aquarium's marine life web page.

Please also see our jellyfish page and All Stings Considered - detailed first aid treatment recommendations for Box jellyfish stings.

Suggested Bibliography

Alam JM, Qasim R. Preliminary studies on biological and hazardous marine toxins from the Karachi coast: (I) biochemical and biological properties of Physalia venom. Abstract #227, International Society of Toxinology Meeting, Singapore, November 3, 1991.

Blow C. Urticaria: a rational GP approach. Practitioner 1997 Feb; 241(1571):80-2, 85.

Brusca RC and Brusca GJ. Invertebrates. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA (1990).

Cormier SM. Physalia venom mediates histamine release from mast cells. The Journal of Experimental Zoology 1981; 218(2):117.

Edwards L, Hessinger DA. Portuguese Man-of-war (Physalia physalis) venom induces calcium influx into cells by permeabilizing plasma membranes. Toxicon 2000; 38:1015-1028.

Hickman CP and Roberts LS. Animal Diversity. Wm. C. Brown, Dubuque, IA (1994).

Kaestner A. Invertebrate Zoology. Interscience Publishers (1964).

Karlsson E, Adem A, Aneiros A, Castaneda O, Harvey M, Jolkkonene M, Sotolongo V. New toxins from marine organisms. The 3rd International Symposium of Neurotoxins and Neurobiology. March 16-21, 1991, Uruguay. Abstracted in Toxicon 1991; 29:1159-1181 (page 1168).

Lane CE. The portuguese man of war. Scientific American 1960; 202(3):158-168.

Lynn M, Snoey E, Bosker G. Anaphylaxis. Allergic Disease Update 1997; 18(25): 246-56.

Shale D., Coldrey J. The Man of War At Sea. Gareth Stevens Publishing, Milwaukee (1987).

Shelton GAB. Electrical Conduction and Behaviour in Simple Invertebrates. Claredon Press, Oxford (1982).

Williamson J, Fenner PJ, Burnett JW, Rifkin JR, editors. Venomous and Poisonous Marine Animals. A Medical and Biological Handbook. University of South Wales Press, Sydney (1996).

Caranx bartholomaei:

Cuvier G, Valenciennes A. 1833. Histoire naturelle des poissons. Tome neuvième. Suite du livre neuvième. Des Scombéroïdes. Hist. Nat. Poiss. i-xxix + 3 pp. + 1-512.

Caretta caretta:

Linnaeus C. 1758. Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Ed. 10, Tomus 1. L. Salvii, Stockholm, Sweden, iv + 826 pp.

Dermochelys coriacea:

Vandelli D. 1761. Epistola de holothurio, et testudine coriacea ad celeberrinum Carolum Linnaeum equitem naturae curiosum Discoridum II. Conzatti, Patavii (Padova). 12 p.

Nomeus gronovii:

Gmelin JF. 1789. Caroli a Linné . . . Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species; cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Editio decimo tertia, aucta, reformata. 3 vols. in 9 parts. Lipsiae, 1788-93. Systema Naturae Linné 1033-1516.

Haedrich RL, 1986. Nomeidae. p. 1183-1188. In Whitehead, PJP, Bauchot, ML, Hureau, JC, Nielsen, J, and Tortonese, E (eds.) Fishes of the North-eastern Atlantic and the Mediterranean. UNESCO, Paris. Vol. 3.

Jenkins RL. Observations on the commensal relationship of nomeus Gronovii with Physalia physalis. Copeia 1983; 1:250-252.