Washi is the Japanese word for the traditional papers made from the long inner fibers of three plants, wa meaning Japanese and shi meaning paper. As Japan rushes with the rest of the world into the 21st Century, and more modern technologies take over, machines produce similar-looking papers which have qualities very different from authentic washi. As of the fall of 1994, there remain roughly 350 families still engaged in the production of paper by hand.

Washi is the Japanese word for the traditional papers made from the long inner fibers of three plants, wa meaning Japanese and shi meaning paper. As Japan rushes with the rest of the world into the 21st Century, and more modern technologies take over, machines produce similar-looking papers which have qualities very different from authentic washi. As of the fall of 1994, there remain roughly 350 families still engaged in the production of paper by hand.

Though paper was originally made in China in the first century, the art was brought to Japan in 610 AD by Buddhist monks who produced it for writting sutras. By the year 800, Japan's skill in papermaking was unrivalled, and from these ancient beginnings have come papers unbelievable in their range of color, texture and design. It was not until the 13th century that knowledge of papermaking reached Europe about 600 years after the Japanese had begun to produce it. By the late 1800's, there were in Japan more than 100,000 families making paper by hand. Then with the introduction from Europe of mechanized papermaking technology and as things "Western" became sought after including curtains (not shoji) and French printmaking papers (not kozo), production declined until by 1983 only 479 papermaking families were left.

Though paper was originally made in China in the first century, the art was brought to Japan in 610 AD by Buddhist monks who produced it for writting sutras. By the year 800, Japan's skill in papermaking was unrivalled, and from these ancient beginnings have come papers unbelievable in their range of color, texture and design. It was not until the 13th century that knowledge of papermaking reached Europe about 600 years after the Japanese had begun to produce it. By the late 1800's, there were in Japan more than 100,000 families making paper by hand. Then with the introduction from Europe of mechanized papermaking technology and as things "Western" became sought after including curtains (not shoji) and French printmaking papers (not kozo), production declined until by 1983 only 479 papermaking families were left.

Ogawa-machi in Saitama Prefecture is about 80 kilometers distant from the center of Tokyo. It is a so-called suburban town.

Ogawa-machi in Saitama Prefecture is about 80 kilometers distant from the center of Tokyo. It is a so-called suburban town.

The paper making industry of Ogawa-machi started more than 1,000 years ago. The name of Ogawa-machi as a paper producing center came to be widely known after the shogunate, the administrative center during the feudal age, was established in Edo (present-day Tokyo). Favored by the location close to Edo, it grew into a center able to meet the huge paper demand of the Edo people who are believed to have numbered about 1,200,000 at the time.

Among the kinds of paper known to have been sent from Ogawa-machi to Edo were paper for keeping records in general, paper for ledgers to be preserved, paper for wrapping dry goods and waterproofed paper for umbrellas.

The town continues at present to be a production center for these kinds of traditional hand-made paper, together with various kinds of newly developed paper.

Nagashisuki:

One of Japan's unique paper making methods. The skill of experienced craftsmen enables Washi of any thickness to be made in a splendid manner.

In what way, then, is Washi made?

The materials used for Washi at the present time are Gampi, Kozo, Kajinoki and Mitsumata. At Ogawa-machi, use is made principally of Kozo and Kajinoki.

The inner barks of three plants, all native to Japan, are used primarily in the making washi.

The inner barks of three plants, all native to Japan, are used primarily in the making washi.

Kozo (paper mulberry) is said to be the masculine element, the protector, thick and strong. It is the most widely used fiber, and the strongest. It is grown as a farm crop, and regenerates annually, so no forests are depleted in the process.

Mitsumata is the "feminine element": graceful, delicate, soft and modest. Mitsumata takes longer to grow and is thus a more expensive paper. It is indigenous to Japan and is also grown as a crop.

Gampi was the earliest and is considered to be the noblest fiber, noted for its richness, dignity and longevity. It has an exquisite natural sheen, and is often made into very thin tissues used in book conservation and chine colle printmaking. Gampi has a natural "sized" finish which does not bleed when written or painted on.

Other fibers such as hemp, abaca, rayon, horsehair, and silver or gold foil are some-times used for paper or mixed in with the other fibers for decorative effect.

The raw material for Kozo. Both Kozo and Kajinoki are defoliated shrubs of the mulberry family which once grew wild in mountainous districts. Nowadays they are all cultivated. The material wood is cut down from autumn to early winter and after being steamed, the bark is removed.

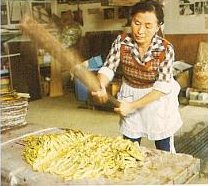

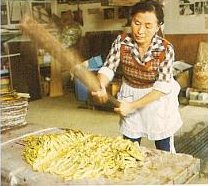

Removing waste material. This bark is boiled in a wooden ash solution, then bleached in river water until it becomes pure white. The fibers are pounded into small pieces with a stick or mallet. This is the principal material for Washi.

Stripping the Kozo bark. One characteristic of Washi differentiating it from paper produced in China is that "neri" is combined. "Neri" is a kind of paste obtained from the root of "tororo-aoi" (hibiscus manihot), a plant resembling "aoi" (hollyhock).

Neri is a kind of "paste" used to join together fibers of equal thinness. The viscosity of this "neri" enables paper to be made in any thickness desired.

Fibers are pounded into small pieces. The paper making method introduced from China was "tamesuki." This is a method in which fibers are scooped up from paper material solution into a "su" or mould (utensil whose bottom is braided with bamboo like a drainboard-it is used to arrange fibers into the form of paper). The water is then drained through the mould.

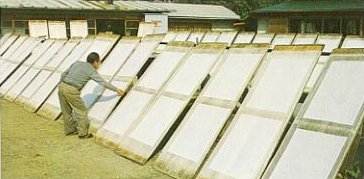

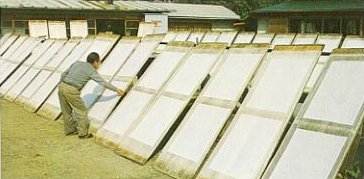

Branches of the (kozo, gampi or mitsumata) bush are trimmed, soaked, the bark removed, and the tough pliant inner bark laboriously separated, cleaned, then pounded and stretched. The addition of the pounded fiber to a liquid solution, combined with tororo-aoi (fermented hibiscus root) as a mucilage, produces a paste-like substance when it is mixed. It is this "paste" which is tossed until evenly spread on a bamboo mesh screen (called a su) to form each sheet of paper. The sheets are piled up wet, and later laid out to dry on wood in the sun or indoors on a heated dryer.

On the other hand, "nagashisuki" was an original method developed in Japan. The mould containing the material solution is agitated forward and backward, and from up to down. Through this operation the fibers intertwine and the paper's layers are formed.

While "tamesuki" is suitable for making thick paper it is possible with "nagashisuki" to adjust thickness freely and to produce extremely thin paper. Nevertheless, since it is an operation requiring the greatest care, even an experienced paper making expert can make no more than 500 sheets in one day.

Natural drying in the sun. The wet paper is laid on top of each other, one by one, and left overnight to remove the water. A press is further used to squeeze out water. Then the paper is spread on a drying board with a brush. It is in this way that Kozo and Kajinoki fibers turn into beautiful "Ogawa Washi."

The difference between Washi and machine-made paper will be touched on briefly.

Paper was first invented in China and brought to Japan by Doncho. Then after a lapse of 150 years, paper was carried along the Silk Road and entered the Samarkand district. It is said that together with the Muslim invasion of Europe, paper was taken to Spain, Italy and Sicily.

This was an age when papyrus and sheepskin parchment were still the most popular for writing purposes. It was not until the 13th to the 15th Century that the method of making paper from live fibers such as hemp and rags began to spread. When wood pulp was invented in the mid-19th Century, machine-made paper such as seen today was born.

Paper made with pulp machines consists of short fibers. Kozo's long fibers would become entangled in the machine's net and cannot be made into paper. Although inferior to Washi in strength and beauty, machine-made paper has the advantage of mass production as ordinary paper throughout the four seasons.

Washi, which is made sheet by sheet through the skill of experienced experts, is characterized by a unique tastefulness. It is impossible to mass-produce it with machines.

It is true that what is called "machine-made Washi" exists. Among examples are the sheets of paper for Japan's currency, 10,000 Yen and 5,000 Yen bills, and stock certificates that have Mitsumata with comparatively short fibers as the material. These 10,000 Yen and 5,000 Yen bills are considered to be the most elegant and sturdiest paper currency in the world, but even then they cannot compare with hand-made Washi. Machine-made paper has excellent suitability, depending on use, but it cannot be expected to possess Washi's inherent tastefulness, suppleness, sturdiness and rich expression as paper.

This is the reason why Japan's Ministry of International Trade and Industry classifies "machine-made Washi" in the category of "machine-made miscellaneous paper."

It was from the mid-16th Century that Washi became known among Europeans. For instance, the famous English diarist John Evelyn has written that he saw "something extremely rare sent back by Christian missionaries who went to Japan and China" and that this was "the paper referred to in 'The New Atlantis' by Francis Bacon." This was "brilliantly shining yellow paper" resembling sheepskin parchment. In other words, it was Japan's Torinoko paper.

Furthermore, Holland's national painter Rembrandt was fascinated by the rich expression possessed by Washi and has left behind etchings made on that paper. This was because a commercial counselor of Holland, the country which monopolized trade with Japan during that period, sent Washi back to his homeland to introduce its superb quality.

The diplomats and scholars who came to Japan from the 17th Century to the early part of the 19th Century, such as Mr. Engelbert Kaempfer (German), Mr. C.P. Thunberg (Dutch), Mr. P.F. Von Siebold (German), Sir J.R. Alcock (British) and Sir H.S. Parkes (British) wrote their respective reports on the techniques of making Washi and these provided a big stimulus to paper making in Europe. British Consul Anzuley, in particular, sent an enthusiastic representation to his government, stating that "the method of cultivating Kozo and the way to make Washi should be transplanted to our country at once."

Washi is the most beautiful paper being made in the world today. It unifies in a splendid manner the users' reciprocal needs for sturdiness, thinness and beauty.

It is certain that the early stage of the paper making technique was introduced from China. But within a short period of time, this inducted technique was fully digested and elevated to a higher cultural level through original ideas and continuos studies. Moreover, instead of using rags as the material, an entirely original paper marking method was developed with the use of plant fibers. Added to this was the national fondness for purity. Development was made of an abundant variety of methods and uses, some of which might make people wonder-"is this really paper?"

Japanese technology and culture took in mutually contradictory needs and, by unifying the contradictions created an "answer" at a higher level. Herein lies a traditional characteristic of the Washi. In this sense, it can be said that Washi is one symbol of the manner in which Japanese culture has progressed.

Warmth -- Literally warmer to the touch, washi feels soft and creates a feeling of warmth to the viewer. Its tactile qualities make it wonderful for invitations and books.

Body -- Since the fibers are left long and pounded and stretched rather than chopped, washi has a deceptive strength. Pure-fiber washi can even be sewn and was used for armour and kimono-lining in earlier times.

Strength -- The length of the fibers and the nature of the raw materials ensure that washi is highly workable when wet. Thus it is excellent for paper mache, and etching in which the paper must be soaked. These long fibers produce a luxurious deckle edge, the rough edge which marks a handmade paper.

Soft translucency -- Kozo and mitsumata are naturally translucent fibers, a quality specific to paper from the East. As such, it is used regularly for the transmission of light.

Absorbency -- The nature of the fibers creates a ready absorption of inks and dyes. Papers that are "pure fiber" and dyed will result in much denser and more vibrant color when fabric or watercolor dyes are applied.

Absorbency -- The nature of the fibers creates a ready absorption of inks and dyes. Papers that are "pure fiber" and dyed will result in much denser and more vibrant color when fabric or watercolor dyes are applied.

Flexibility -- Since the fibers position themselves at random, there is no real grain to washi. This gives the paper a resistance to creasing, wrinkling and tearing - and means it can be used more like cloth, for covering books, or boxes etc.

Lightness -- Washi weighs much less than other papers of equal thickness. As a paper for books, it can create texts of apparent weightlessness.

Low acidity -- Traditionally-made Japanese papers are truly acid-free if they are unbleached and unsized. Examples of printed papers exist in perfect condition in Japan from 1000 years ago. Today, papers from the village of Kurotani are among the finest archival papers.

Decoration -- For centuries, colorful designs applied by woodblock or handcut stencils have created vividly characteristic papers, for decorative use. Recently, silkscreened chiyogami (small repeated-patterned paper) is available in an unbelievable range and widely used by craftspeople. Although made by machine, the quality available is about 70% kozo and comes in hundreds of patterns.

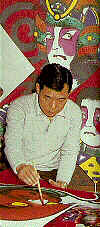

Printing -- The special absorbency, strength and texture of washi results in unique images. Traditional Japanese printing was done by woodblock, but washi is also effectively used for wood engraving, linoblock, or letterpress techniques. It responds well to embossing, and can be used effectively for multi-color lithographs and chine-colle (etching). Rembrandt often used Japanese paper for his fine etchings, David Milne painted on gampi tissue, and Canadian Inuit have for some years used washi to elicit the best results in their stone and stencil prints.

Collage -- The broad range of textures, colours and patterns of the paper, and its wet strength, make washi a highly appropriate material for collage. Chiri papers, with their bark fragments and chiyogami are favorites for collage though all washi is suitable. In recent years, artists often paint watercolor over richly collaged "canvases".

Lighting -- Washi has been used traditionally in screens and lamps and more recently in shutters and blinds to utilize its translucency. Mino, 'silk', seikaiha and unryu are commonly used. After being moistened, washi will shrink slightly when it dries, thereby tightening it more securely on a frame.

Bookbinding-- Washi's strength and flexibility make it excellent for book covers and end papers or for book sleeves and boxes. Its wet strength makes it ideal repair tissue. Kyoseishi, ungei heavy, "silk", chiri and chiyogami are among those strong enough for book covers. Usumino and Kurotani #16 make especially strong repair tissue, but tengu, mino, and yame are also suitable.

Bookbinding-- Washi's strength and flexibility make it excellent for book covers and end papers or for book sleeves and boxes. Its wet strength makes it ideal repair tissue. Kyoseishi, ungei heavy, "silk", chiri and chiyogami are among those strong enough for book covers. Usumino and Kurotani #16 make especially strong repair tissue, but tengu, mino, and yame are also suitable.

Sumi-e and Shodo -- Japanese printing and brush-writing using sumi, a natural carbon-based ink, are at their best on washi. Ise, kai, mino and all Kurotani papers are a few particular favourites for this use.

Many traditional uses of the paper have endured: origami, kites, doll and umbrella-making and unparalleled packaging. Today, its uses are limitless: paper jewellery; to cover mats in framing; used as a background for photography and to develop photographs on; to cover walls and furniture; to produce memorable wedding invitations and for a host of graphic design and public relations promotions.

As time goes on, modern technology replaces much of the traditional process. Still there are those papermakers left who will not compromise.

Washi is the Japanese word for the traditional papers made from the long inner fibers of three plants, wa meaning Japanese and shi meaning paper. As Japan rushes with the rest of the world into the 21st Century, and more modern technologies take over, machines produce similar-looking papers which have qualities very different from authentic washi. As of the fall of 1994, there remain roughly 350 families still engaged in the production of paper by hand.

Washi is the Japanese word for the traditional papers made from the long inner fibers of three plants, wa meaning Japanese and shi meaning paper. As Japan rushes with the rest of the world into the 21st Century, and more modern technologies take over, machines produce similar-looking papers which have qualities very different from authentic washi. As of the fall of 1994, there remain roughly 350 families still engaged in the production of paper by hand. Though paper was originally made in China in the first century, the art was brought to Japan in 610 AD by Buddhist monks who produced it for writting sutras. By the year 800, Japan's skill in papermaking was unrivalled, and from these ancient beginnings have come papers unbelievable in their range of color, texture and design. It was not until the 13th century that knowledge of papermaking reached Europe about 600 years after the Japanese had begun to produce it. By the late 1800's, there were in Japan more than 100,000 families making paper by hand. Then with the introduction from Europe of mechanized papermaking technology and as things "Western" became sought after including curtains (not shoji) and French printmaking papers (not kozo), production declined until by 1983 only 479 papermaking families were left.

Though paper was originally made in China in the first century, the art was brought to Japan in 610 AD by Buddhist monks who produced it for writting sutras. By the year 800, Japan's skill in papermaking was unrivalled, and from these ancient beginnings have come papers unbelievable in their range of color, texture and design. It was not until the 13th century that knowledge of papermaking reached Europe about 600 years after the Japanese had begun to produce it. By the late 1800's, there were in Japan more than 100,000 families making paper by hand. Then with the introduction from Europe of mechanized papermaking technology and as things "Western" became sought after including curtains (not shoji) and French printmaking papers (not kozo), production declined until by 1983 only 479 papermaking families were left.  Ogawa-machi in Saitama Prefecture is about 80 kilometers distant from the center of Tokyo. It is a so-called suburban town.

Ogawa-machi in Saitama Prefecture is about 80 kilometers distant from the center of Tokyo. It is a so-called suburban town.  The inner barks of three plants, all native to Japan, are used primarily in the making washi.

The inner barks of three plants, all native to Japan, are used primarily in the making washi.

Absorbency -- The nature of the fibers creates a ready absorption of inks and dyes. Papers that are "pure fiber" and dyed will result in much denser and more vibrant color when fabric or watercolor dyes are applied.

Absorbency -- The nature of the fibers creates a ready absorption of inks and dyes. Papers that are "pure fiber" and dyed will result in much denser and more vibrant color when fabric or watercolor dyes are applied.

Bookbinding-- Washi's strength and flexibility make it excellent for book covers and end papers or for book sleeves and boxes. Its wet strength makes it ideal repair tissue. Kyoseishi, ungei heavy, "silk", chiri and chiyogami are among those strong enough for book covers. Usumino and Kurotani #16 make especially strong repair tissue, but tengu, mino, and yame are also suitable.

Bookbinding-- Washi's strength and flexibility make it excellent for book covers and end papers or for book sleeves and boxes. Its wet strength makes it ideal repair tissue. Kyoseishi, ungei heavy, "silk", chiri and chiyogami are among those strong enough for book covers. Usumino and Kurotani #16 make especially strong repair tissue, but tengu, mino, and yame are also suitable.