Skin Cancer in Solid-Organ Transplant Patient

Continued advances in solid-organ transplantation have improved long-term mortality among transplant patients. More than 140,000 organ recipients are living in the United States (US), with a similar number of patients on a waiting list. However, transplantation and iatrogenic immunosuppression are associated with adverse events and impact on morbidity, mortality, and patients' quality of life. While there is an overall increased risk of malignancy, skin cancers and particularly non-melanoma skin cancers (NMSCs) are most frequently observed (Figures 1 and 2). The risk of basal cell carcinoma (BCC) and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) is 10 and 65 times greater compared to non-transplant patients, respectively. Importantly, the ratio of BCC to SCC is reversed among Caucasian patients, ranging from 1:1.2 to 1:15. The rate of melanoma among renal transplants is also 3.6 times greater compared to immunocompetent patients. Kaposi's sarcoma accounted for 79% of cancers among non-White patients in South Africa observed over a mean follow-up period of 6.3 years.

With the exception of Kaposi's sarcoma, a significant amount of data on the incidence of NMSCs and melanoma has been derived from predominately Caucasian populations in European countries, Australia, and the US. In contrast, limited information addressing the extent and types of cutaneous malignancies in transplant patients with ethnic skin has been published thus far. One study showed a statistically significant decrease in 3-year cumulative incidence of NMSC in African American (AA) and Asian renal recipients as compared to Caucasians, with a relative risk of 0.06 and 0.11, respectively. A 10-year retrospective analysis of 6271 heart-transplant patients from 32 US transplant centers demonstrated an extremely low incidence of skin cancer among non-Caucasian patients (AA, Hispanic, Middle Eastern, Indian, Asian, and Native American), which accounted for 15% of the study population. A 10-year period free of cancer among this non-Caucasian population was 99.2%. This data may become clinically important since it has been estimated that Hispanics, Asians, and blacks will make up 50% of the US population by the year 2050.

After the first NMSC, up to 80% of transplant patients will develop second primary NMSC within 3 years. Furthermore, the risk of developing NMSC is cumulative after the transplant and gradually increases with time.1 The degree of immunosuppression is also an important risk factor. Heart and lung transplant patients, who require higher levels of immunosuppression, have an increased propensity to develop NMSC as compared to renal and liver transplants.

Fitzpatrick Skin Phototype (SPT) is an independent risk factor for NMSC development. The most recent study showed the cumulative incidence of SCC at 10 years to be 51% in patients with SPT I and 8% in SPT VI. Non-Caucasians constituted less than 8% of the study sample including only 11 (1.6%) AA and 26 (3.8%) Hispanic patients. Of note, no SCCs were observed among AA and four SCCs were diagnosed in Hispanic patients. This study also highlighted an important concept of wide variation of SPT within a particular ethnic group. The contribution of ultraviolet (UV) light to NMSC development is highlighted by its greater incidence in transplant patients in Australia as compared to other Western countries. UV-related risk factors in the post-transplant period include sunburn as a child, Fitzpatrick SPTs I through III, residing in a hot climate for more than 30 years, and significant prior UV exposure. Voriconazole, which has potent photosensitizing properties, is a potential contributing factor. In lung-transplant patients, the duration of voriconazole therapy was an independent risk factor for developing SCC, which can have more aggressive behavior. While the role of human papillomavirus (HPV) in SCC pathogenesis has not been entirely elucidated, several studies suggest its potential role. Transplanted patients harbor a greater quantity of various HPVs - particularly the beta type. Moreover, seropositivity to beta-type HPV37 was associated with a significantly increased risk of SCC in the post-transplant period (odds ratio 2.0, 95% confidence interval 1.2-3.4). Additionally, three genetic variants of TMC8, the gene associated with epidermodysplasia verruciformis and predisposition to the development of numerous warts and SCCs, were associated with greater seropositivity to two species of beta HPV viruses.

Significant impairment of cutaneous immunosurveillance has been suspected to be the main culprit for the propensity to develop multiple NMSCs and SCC in particular. However, more light has been shed on the direct effect of immunosuppressive drugs, irrespective of their immunosuppressive properties. Cyclosporine diminishes the expression of tumor suppressor PTEN and UVB-induced DNA repair, thereby facilitating UVB-driven carcinogenesis. Similarly, in in vitro cell-culture, tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil also inhibit UVB-induced repair of cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers. Both immunosuppressant drugs also inhibit UVB-induced apoptosis, which serves as a major checkpoint in preventing the uninhibited proliferation of keratinocytes. Azathioprine causes oxidative DNA damage in conjunction with UVA light.

Thus far, there has been a lack of effective and consistent management strategies for patients with numerous NMSCs. Pre-emptive, frequent patient monitoring with surgical or non-surgical interventions is the current mainstay of treatment. However, besides the reduction of immunosuppression, few systemic agents diminish the overall tumor burden. Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors are potentially helpful in reducing the development of SCCs. Five prospective clinical trials highlighted the ability of sirolimus to diminish the incidence of NMSC. Earlier transition to mTOR inhibitor-based immunosuppressive regimen may be more chemopreventative. Two large, randomized controlled clinical trials showed a significant reduction of NMSC incidence in those patients who were switched to an mTOR inhibitor after their first NMSC. However, there is a considerable incidence of side effects with up to 40% of patients discontinuing mTOR inhibitors, which limits its use.

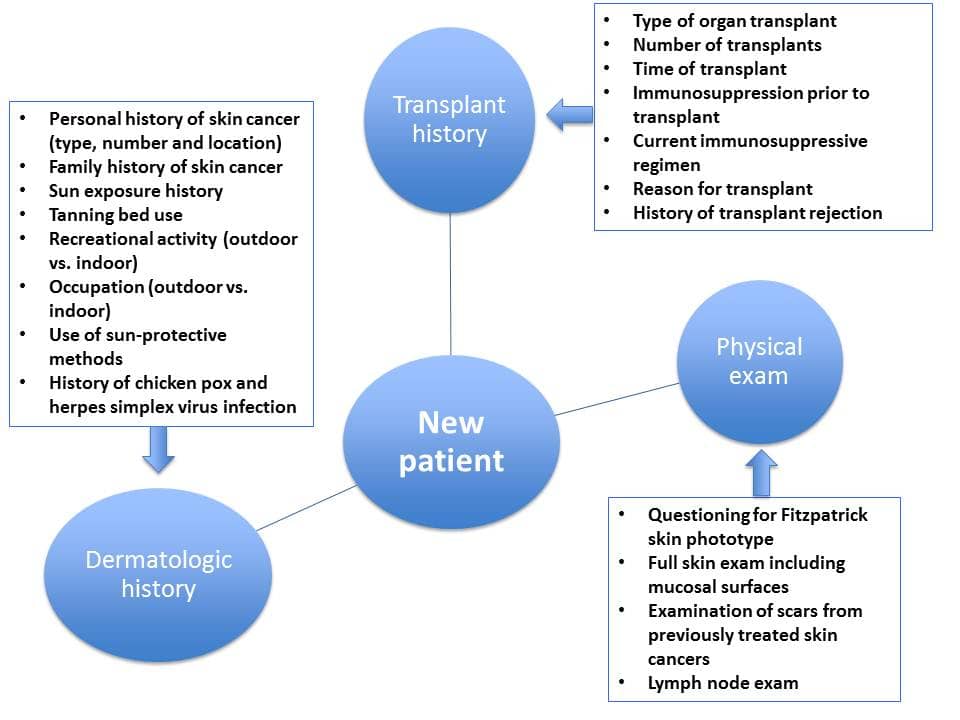

Further research efforts are needed to better understand the underlying pathophysiology of NMSCs in this patient population and to identify potential targets for prevention and treatment. In the interim, patient education and continued close surveillance are essential aspects of patient management (Figure 3).