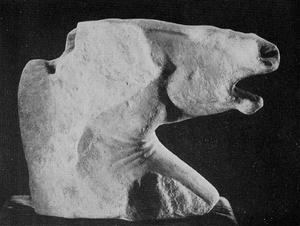

A Greek marble Head of a horse

A fragmentary head of a horse1 in Greek marble has recently been added to the collection of ancient sculpture in the Detroit Institute of Arts as a gift of the Founders Society. Its spirited vitality. which immediately impresses the spectator brings to mind the words of Xenophon, written in the fourth century before Christ: "A prancing horse is a thing so graceful, terrible and astonishing that it rivets the gaze of all beholders, young and old alike. This is the atti-tude in which artists represent the horse on which gods and heroes ride."2 The horse, from the time of its introduction from the East into Greece in the Minoan period, was a favorite subject with the Greek artist. It was hardly less popular with the Romans.

The new acquisition is executed in a fine-grained white marble, now tinged with a golden patina, probably from the quarries on Mount Pentelicon near Athens. The surface of the oblique cut across the neck does not indicate clearly whether the head was once part of a complete figure of a horse or is in itself complete, intended for some special use. The latter seems most likely as the head is pierced by a circular opening through the neck and nose to allow the passage of water. It was undoubtedly used in ancient times as a fountain decoration and it is tempting to think that it once formed part of a large group, perhaps Poseidon rising from the water in his chariot drawn by sea horses spouting water. An alternative is that this head was placed in a somewhat similar group in the triangular pediment of a shrine or temple, after the manner of the Parthenon where the sun god, Helios, drives his horsedrawn chariot upward from the sea, and Selene, Goddess of the Moon, sinks into the sea with her horses, these groups filling the extremities of the triangular pedimental space. The original use of the head in a pedimental group does not actually exclude its later reuse in a fountain.

Traditionally the head was found in the northeastern part of Rome be-tween the Quirinal and Pincian hills where the more recent gardens and properties of the Villa Ludovisi and the Villa Massimo were the successors of the ancient gardens of Sallust, the Hortus Sallustiani, one of the great series of parks and gardens, public and private, which encircled the ancient city. From the first century of the Christian era the gardens of Sal-lust were crown property and a favorite residence of the emperors who embellished them with works of art and watered them with fountains. The sculptures of these gardens were in large part the spoils of Greece by conquest, theft, or purchase, although some were Roman copies after Greek originals or original works by Roman artists. Chance discovery rather than organized excavation has recovered numerous noted sculptures in this locality. It is not too much to presume that the Detroit head of a horse, said to be from the same region, is a Greek work, brought to Rome in late Republican or early Imperial times when the spoliation of Greece was common and almost continuous, and although it may have once been part of a pedimental group, it alone or the whole group was adapted by the Romans for use as a fountain decoration in the public gardens.

The determination of the date of execution of this head might be easier and more certain where it less damaged.3 Viewed in relation to representations of the horse of more or less certain dating, the Detroit acquisition appears to represent the type of horse found in the second half of the fifth century before Christ on the Parthenon, but it has the somewhat more slender proportions of the spirited horses on the Alexander Sarcophagus of the last third of the fourth century. If the head was originally a fountain piece, it is unlikely that it antedates the early years of the Hellenistic age when fountains in private houses and public places became more common and more elaborate.

FRANCIS W. ROBINSON

1 Accession Number: 39.602. Marble. Height: 11% inches; Length: 151/1: inches. Formerly Colleetion Giacomo Nunez, Rome.

2 XenOphon, on tbs Art 0/ Horwmamln‘p, xi, 8-9, in Scripta Minom, translated by Ii. C. Marchant. London, 1925. p. 355.

3 One eye, the cars, mane and forclock, as well as the metal bridle, are gone; the Other eye and other parts of the surface are much worn. Apparently the ears and forclock were worked sepxaratcly and attached as indicated by various cuttings and sockets in the crown of the head; these are perhaps the result of later restorations and reworkings.