Bingata

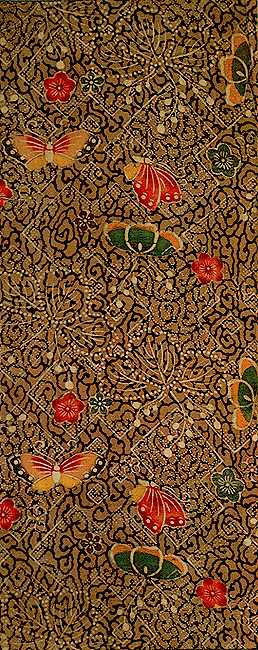

Ryukyu Bingata are vivid and beautiful dyed goods expressing the rich colors of Okinawa's nature.

Ryukyu Bingata are vivid and beautiful dyed goods expressing the rich colors of Okinawa's nature.

Its origin is not known but the dyeing techniques were transmitted by means of international trade from China, India and Java and their prints in the 14th−15th centuries. Bingata was a formal dress for the royal and shizoku (warriors class) families. The royal family wore yellow bingata while the nobles wore light blue and the common people were allowed to wear it when they cerebrated longevity.

Main patterns are as follows:"Udun-gata" for the royal and shizoku families, "Dounchi-gata" for the upper shizoku, "Shuri-gata" for shizoku in general, "Wakashu-gata" for families of upper shizoku, "Ganji-gata" for children. "Naha-gata" and "Tomari-gata" were for common people and export purposes. The aristocrats used the Bingata of "Chirimen" (silk crepe) or "Rinzu" (figured satin) with picturesque and multi-colored large designs on a white background or light yellowish color. The common people used cotton cloth of oboro-gata dyed in either 5 colors (iro-oboro) or 2 colors (indigo and black ).

There are two methods of Bingata dyeing, namely Kata-zome (stencil dyeing) and Tsutsugaki-zome (cylinder dyeing). Paste is placed on the stencil or cylinder to prevent the part from dyeing over pigments or vegetable dyestuff that are applied for coloring. Aigata (indigo blue bingata) is dyed with some shades of indigo.

Kata-zome is mainly used for dyeing garments while Tsutsugaki is often used for furoshiki (wrapping cloth) or a stage curtain for Ryukyu dance. Furoshiki is used for the wedding ceremony and its popular patterns include Sho-chiku-bai (pine, bamboo and plum trees), Peony and Iris, while the curtain patters are often Sho-chiku-bai and Tsuru-kame (crane and turtle).The dyeing methods are as follows:

Uburu-gata

Patterns on background using Someji-gata and Hakuji-gata.

Someji-gata

Dye patterns and background with one paste placing

Kaeshi-gata

Dye with Hakuji-gata once, then dye background with paste placing of the patterns

Hakuji-gata

One paste placing, dyeing the patterns leaving only the background white.

Okinawa Bingata

Okinawan's dyeing technique called bingata. The islands of Okinawa were originally a separate kingdom called Ryukyu. This kingdom traded with China, Korea, Japan and Southeast Asia but had a unique culture all its own. Some of the most famous textiles made in the Ryukyu Kingdom were bingata dyed textiles and basho-fu (a woven abaca fiber textile).

Bingata, thought to be at least 500 years old, is a dyed fabric that uses stencil paper patterns. Although the word bingata doesn't appear in old documents, it used to be called katachichi, which meant "to apply patterns," or hana-nunu, a flower cloth.

The first person to actually use the word bingata was a man called Iha Fuyu (1876-1947). Another historian, Kanjun Higashionna (1882-1963) thought the name came from Bengal, India, where the fabric was assumed to have originated. Finally, Keisuke Serizawa (1895-1984), a dyework artisan, said that bingata meant "colored designs," as he believed that "bin" meant colors and "kata" (or gata) meant designs.

(Coutesy of the Prefectual Museum)

It is beleived that during the Ryukyuan Dynasty, dyeing supplies were issued only by the King's office. The patterns and designs were made by the Drawing and Design Planning Office. Only royal family members and the upper class people in Naha were allowed to wear a bingata kimono. Women of the higher classes were said to have kept the stencil paper patterns used to make their kimono so that no other woman could wear the same bingata pattern.

The oldest piece of bingata cloth, found on Kume Island, was a silk undergarment said to have been worn by the daughter of a chieftain named Ishikawa, dating back to the reign of King Sho En (1470-76).

Bingata is a dyeing technique that is unique to the Ryukyu Islands and continues to be made as a traditional art in Okinawa today. The bold patterns and bright red, yellow, blue and green colors of bingata are dyed with the aid of a starch called nori. This nori can be applied to the cloth through a pattern stencil or freehand, pressed through a bag like that of a cake decorator! This latter process is called tsutsugaki. Both stencil dyeing and tsutsugaki are examples of resist-dyeing. Dyes cannot penetrate through the sections of cloth that have been covered with the nori starch, so they retain their original color, even after dyeing. The dyes are applied to the cloth one by one. Finally, when the patterns are completed, the pattern sections are covered with nori and the whole cloth is dyed the background color.

Originally, bingata could be worn only by aristocratic social classes, such as kings and warrior families. Bingata textiles were also used for the costumes of dancers who welcomed envoys from China or from the Tokugawa Shogunate in Edo (today's Tokyo). Especially interesting are the motifs (designs) on bingata textiles. Though bingata is a process unique to the Ryukyu islands, bingata textiles are often decorated with typical Japanese motifs, such as cherry blossoms, pine trees and wisteria. In one textile, we can see the cross-cultural influences of both Southeast Asian-style dyeing techniques and Japanese patterns!

Ushinchi

During the period of Ryukyu, there was a unique way to wear kimono. This was called "Ushinchi". This means to tuck in Ryukyu language. In Ushinchi style, people do not use obi. Probably this style was made in order to beat the severe southern heat.

The daughters of samurai wore a kind of kimono, which had beautiful colors of yellow and red. Such patterns of kimono are called bingata. Today, Okinawan's wear bingata gennerally only when they perform their traditional dance.

Kasuri

Common people of Ryukyu kingdom wore clothes called Kasuri, which had patterns of triangles and squares. Today, it is generally only worn when they play the part of an old woman in a Ryukyu play.

Basho-fu (Banana Fiber Textiles)

You have probably never heard of basho, but it is a kind of banana plant. Though similar to the plants from which we get bananas for eating, basho (or more specifically, ito basho, "thread banana") plants are remarkable for their fibrous stems instead of for their fruit. Basho plants grow into "trees" of about two meters in height. Botanically speaking, however, they are not actually trees but large herbaceous plants. Banana species include some of the largest herbaceous plants in the world! The fibers in the "trunks" of basho plants can be split into fine strands, tied together into thread, and woven into cloth. This cloth is what is call basho-fu. Basho-fu has long been favored for summer kimonos because of its airiness and smooth, crisp surface. Like linen, hemp, ramie, and other "bast fibers" (long vegetable fibers), basho-fu does not stick to the skin in hot weather, making it perfectly suited to the hot Okinawan climate. In the old days, bolts of plain-colored, striped and kasuri (ikat) basho-fu were woven in numerous locations across the Ryukyu islands and were used as tribute payments to the Okinawan royalty. In those days, basho-fu was worn by everyone from kings to commoners. Nowadays, however, basho-fu is a luxury cloth that is made only in the village of Kijoka, on the island of Okinawa.